To the Rescue of Paul Gauguin

A Rejection of Woke 'Entartete' Art

Wild Thing: A Life of Paul Gauguin by Sue Prideaux. Faber & Faber 2024, ISBN 978-0-5713-6593-7

He lapped up life daringly, mastered the art of rebellion, and looked far beyond the horizon to find adventure whilst looking to rest his wandering soul. Just before the implacable woke crowd could ‘cancel’ him, biographer Sue Prideaux snatched Paul Gauguin from its claws.

The French postimpressionist painter seemed ripe for the picking: the perfect candidate to be knocked off his pedestal, thrown from his perch, and relegated to the scrapheap of art history. It was not for a lack of trying that the über-politically correct posse failed in its pursuit.

Even The Conversation, an online platform of considerable repute, could not resist the temptation to fall in with, and out-shout, the philistine crowd and found its necessary to depict Paul Gauguin as ‘a violent paedophile, serial rapist, fist-swinging thug, and sex tourist’ who infected his children with syphilis. British art critic Alistair Brooke, who ought to know better (but must also make a living) had to be mobilised as well to sketch Gauguin as ‘a nineteenth century Harvey Weinstein’. How original.

In Wild Thing: A Life of Paul Gauguin, Anglo-Norwegian biographer Sue Prideaux disproves several of the wilder accusations hurled at Gauguin and gives the Frenchman the fair shake he deserves. As a writer, Ms Prideaux is drawn to wild men. She won wide acclaim with her biographies of nineteenth-century iconoclasts Friedrich Nietzsche (I am Dynamite!) and Edvard Munch (Behind the Scream). Ms Prideaux’ godmother sat for Much whilst her grandmother was muse to the Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen.

Teeth Examined

Wild Thing starts with an inspection of Paul Gauguin’s teeth, found in 2000 at the bottom of a well, locked in a glass jar, near the last bamboo hut of the painter in French Polynesia. Sent to the Human Genome Project for examination, the secreted teeth were confirmed to be Gauguin’s and helped rebut the persistent charge that the painter had merrily or otherwise spread syphilis around the pristine South Seas.

The discarded teeth contained no traces of arsenic or mercury. At the time, the standard treatment for syphilis included pills with compounds of both chemicals. The discovery prompted Ms Prideaux to ask what other myths surrounding Gauguin may prove false.

In this endeavour, she was helped by a handwritten 213-page manuscript that resurfaced (after being ‘forgotten’ for over a century) in 2020 and in which Gauguin describes his last two years on the Marquesas Islands. The memoir Avant et après (Before and After, published in the US in 1903 as Intimate Journals)) shows Gauguin with his body tormented by disease and dulled by morphine, and his mind consumed by anger over the incompetence and malice of French colonial administrators.

As promised in the book’s title, Ms Prideaux takes the reader along on a wild rollercoaster ride of Gauguin’s restless and short life – he died aged 54 – from France to locales as far-flung as Panama where he helped dig the canal; Martinique where he suffered from bouts of malaria and lived in a leaky ‘negro hut’ whilst waiting for repatriation; and, of course French Polynesia where he hoped to find release from the disillusionment brought by the ruthless art critics of Paris, minders of convention and propriety, who savagely tore into the artists’ work.

Powerful Women

Gauguin’s childhood was forged by two powerful women. His grandmother Flora Tristán, admired by Karl Marx and survivor of an attempt on her life by a jealous and abusive husband, was to become a leading suffragette. His mother Aline was widowed whilst on a voyage to Peru where she was to unsuccessfully claim her part of the family’s inheritance. Her husband Clovis, scion of a moneyed family of industrialists, had been a journalist forced into exile during the revolutionary upheavals of 1848, the year their son Paul was born.

Though Aline Gauguin née Marie Chazal Tristán failed to secure part of the aristocratic Tristán Moscoso family fortune, she published a travelogue of her experiences and impression of Peru which became a bestseller and launched her literary career.

During their six years’ sojourn in Peru, Paul and his older sister Marie enjoyed a care-free Rousseauian childhood, Ms Gauguin was busy fending off the advances of her paternal great-uncle whose son-in-law Rufino Echenique would soon become the twelfth president of the country. The Gauguins were invited to take up residence in the presidential palace but had to hurriedly flee the country after the Echenique presidency was cut short and overthrown during the Liberal Revolution of 1855.

Savage from Peru

Back in France, the young Paul would caution would-be school bullies that he was ‘a savage from Peru’ which apparently worked wonders on their demeanour. At age 14, after doing poorly at school, Paul entered a naval preparatory academy before signing up as an assistant navigator in the merchant marine. After a stint in the French navy, he returned to Paris in 1871 where he secured a job at the stock exchange. Here, He not only earned a good salary as a broker (some $140,000 annually in today’s money) but doubled his income by dabbling in the art market.

Meanwhile, Gauguin had married the Danish Mette-Sophie Gad with whom he fathered five children. After the stock market crash of 1882, the Gauguins moved to Denmark where Paul tried his luck as a tarpaulin salesman. However, the Danes were uninterested in French tarp from someone unable to speak the language. The in-laws’ cranky disposition didn’t help either.

Mette-Sophie sustained the family for a few years as its sole breadwinner whilst Paul concentrated on painting which he had begun as a pastime around 1873, albeit without much success. Even lacking any formal education in the arts, Gauguin blazed his own sui generis trail far outside the well-trodden path of fashionable ‘isms’. However, not everybody was appreciative of his flattened perspectives and outlandish colours. The impressionist Claude Monet dismissed Gauguin’s work as ‘clamorous and vulgar’.

The marriage soon fell apart with Paul returning to France and, in near-desperation and penniless, embarking on a ship to Panama where he hoped to find work as a digger on the canal. In a letter to his estranged wife, he wrote: “I have to dig from five-thirty in the morning to six in the evening, under the tropical sun and rain. At night I am devoured by mosquitoes.” His only security was provided by standing French policy that guaranteed expatriates whose luck had run out a ticket home at state expense.

Stopping off briefly at Martinique, Gauguin arrived back in France and managed to get his Caribbean paintings exhibited at a Paris gallery where they were spotted and admired by Vincent van Gogh and his brother Theo, owner of Goupil & Cie auction house and a well-known art dealer. Theo van Gogh – mesmerised by the painter’s use of ‘otherworldly’ light and colour – not only purchased three paintings but also introduced Gauguin to wealthy collectors.

Van Gogh’s Blade

Vincent and Paul became friends and shared a house in Arles for nine weeks in 1888. The interlude came to an abrupt end when Gauguin, suffering from sensory overload and the mood swings of his companion, announced his immediate departure which was met with flying kitchenware and a knife attack – reportedly the very same blade the Dutch painter used later that evening to severe his own ear. The following day, Van Gogh was hospitalised and Gauguin left Arles. Whilst in France, Gauguin also met Paul Cézanne, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas who became a great admirer and a lifelong friend.

Using the proceeds from sales and events organised by Theo van Gogh and Edgar Degas, Gauguin travelled to Tahiti in 1891, promising Mette-Sophie and his five children to make his fortune there and return home. However, the idyll he hoped to find was not to be. Trying to ‘escape everything that is artificial and conventional’, the artist instead found a local culture subdued and corrupted by its indifferent French overlords.

There was no fruit to freely pick from the trees since the trees had owners; no tubers to pull from the ground because every square inch of land was accounted for; and no animals fit for the pot to chase because, they too, belonged to someone. Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Noble Savage had become detached from his roots and morphed into a grubby trader.

However, this did not prevent Gauguin from enjoying the pleasures of the South Seas as first titillatingly described in the logbooks of Captain James Cook. The more ‘troubling’ part of Gauguin’s legacy concerns his exploits with exotic Polynesian girls, some as young as thirteen or fourteen and with whom he fathered children.

Androgyne or Predator?

Before Mette-Sophie formally broke off their relationship in 1894, Gauguin remained faithful to his wife. In her scintillating biography, Ms Prideaux tries to unravel and make sense of countless mixed signals. Without casting moral judgment, she depicts the painter advising a young female art student to avoid the trappings of marriage and start thinking like an ‘androgyne, without sex’.

A few chapters on, the reader finds Gaugin extolling the virtues of his 14-year-old Tahitian bride Teha’amana who is blessed with ‘the gift of silence’ as she prepares his food and dispenses oral pleasures in return for ‘a frock worth not ten francs a month.’

Another myth Ms Prideaux skilfully dispels concerns Gauguin as the ruthless French colonialist. During his stay, first in Tahiti and later on the even more remote Marquesas islands, Gauguin became a thorn in the imperial flesh, tirelessly calling out the absurdities of French rule, the idiocy of its edicts, and the ineptitude of its officials.

His vehement criticism at the lack of respect for, and understanding of, the local culture prompted Gauguin to organise a tax strike on his island and encouraged settlers, traders, and planter to follow suit. He was hauled before the local magistrate and fined 500 francs and sentenced to three months in prison. Gauguin immediately filed an appeal in faraway Papeete, the administrative capital of French Polynesia, but died before his case was heard.

After a visit home to sell his paintings in 1893, Gauguin returned to Tahiti two years later – this time to stay. Back in Papeete, he carved out a reasonably comfortable life through the sale of his paintings and by taking up odd office jobs whenever funds ran low, all the while dreaming of the Marquesas, the forlorn archipelago of twelve island at the very fringe of the French empire. Here, he hoped to find the South Seas charm that had eluded him on Tahiti.

Marquesas

By 1901, Gauguin had raised enough cash to make the trip – a week by steamer – to Atuona on Hiva Oa. Here, he managed to buy a plot in the centre of the village and erected a well-made house on it. However, even the distant Marquesas had agonised under French rule. Through disease (mainly tuberculosis) introduced by missionaries, the archipelago’s eighteenth-century population had crashed from an estimated 80,000 to about 4,000 when Gauguin showed up.

Finding even tiny Atuona too bustling and too French for his taste, the painter encircled his ‘House of Pleasure’ with a wall of greenery and statues of the local monseigneur and his 14-year-old mistress.

The statue of the bishop ‘Père Paillard’ is on exhibit at the National Art Gallery in Washington and its smaller sibling ‘Thérèse’ was auctioned in 2015 by Christie’s in New York for almost $31 million. In Atuona, Gauguin regained his vigour, finishing more than sixty paintings and dispatching most of them to France.

Looking back on his life in Après et avant’, Gauguin likens himself to ‘a ship tossed about by every wind’. However, he steered a course that would point the way for others to explore depths in form, style, and composition yet unvisited. Gauguin’s work prompted Pablo Picasso to look at African art and its patterns which birthed cubism, blazing a trail for modern art.

A new Gauguin biography is an occurrence likely to happen only once in a generation. Sue Prideaux’ Wild Thing is masterfully written with insights gleaned from the rediscovered manuscript, and extensive travel to the places where the painter found his inspiration. The biographer doesn’t condemn or condone but places the artist in his era and extracting glimpses of his mind from Gauguin’s own writings.

‘Entartete’ Art

In the 1920s, the Nazi Party introduced the term ‘degenerate art’ (Entartete Kunst) to heap together all expressions of art it considered offensive to the ‘German volk’. Work so designated was banned from museums and public space. Artists suspected of undermining the ‘German spirit’ suffered numerous sanctions: they not only lost their teaching positions at art academies, but were also forbidden to sell or exhibit their art, and, in some cases, prevented from working.

The cleansing of art by applying today’s enlightened societal values to past behaviour now considered reprehensible, as advocated and vigorously pursued by ‘woke’ revisionists, merely updates Nazi practices. Whilst the conduct, attitude, and dealings of gifted artists has often been far from acceptable by today’s standards, their work stands as a testament human creativity, sensitivity, and ingenuity – including all the character flaws of the makers.

Erasing such artists and their work from society and public view, and wiping them from our collective memory and the human canon, is an act of deliberate destruction on par with the worst excesses of the islamic zealots who burned over four thousand historic manuscripts at the Timbuktu Library and blasted the Buddhas of Bamiyan with explosives and grenades – or, indeed, the christian zealots who destroyed the papyrus rolls of antiquity by scrubbing out the original texts and overwriting these with religious prose.

| Artist ‘Cancelled’ | Alleged Reasons | |

|---|---|---|

| Edgar Degas (1834-1917) | French impressionist painter and sculptor (’The Little Dancer’). During the infamous Dreyfus Affair which split public opinion throughout France, Degas became a virulent antisemitic, disavowing his Jewish friends. |  |

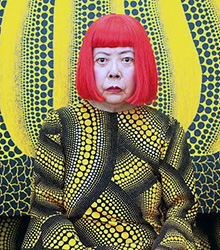

| Yayoi Kusama (1929) | Japanese sculptor and recognised as the world’s most successful living artist. Outcast for racism after the publication in 2002 of her autobiography in which she stereotyped black people as possessing ‘animalistic sex techniques’ and ‘a distinctive smell’. |  |

| Salvador Dalí (1904-1989) | Spanish surrealist artist whose life resembled the bizarre yet sublime work he produced as a painter, sculptor, photographer, cineast, author, and fashion designer, amongst others. Condemned for his public support of the Franco-regime in Spain, his necrophilic impulses, never acted on, and fascination with slavery and human sacrifice. |  |

| Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) | Spanish painter and sculptor sanctioned for sexual harassment of the models who posed in his studio and with whom he often, almost invariably, had affairs. Each of Picasso’s many women influenced his style. Also accused of abducting and mentally abusing his lovers and of destroying the career of painter Françoise Gilot after she dumped him. |  |

Cover photo: Paul Gauguin’s 1892 Arearea canvas, aka ‘The Red Dog Painting’, exhibited a year later at the Durand-Ruel exhibition in Paris and now part of the collection of the Muséee d’Orsay.

Photo credits

- © 2023 Photo Sue Prideaux by Douglas Fry / Faber and Faber

- © 2000 Photo Gauguin’s tomb on Hiva Oa by Sardon

- Photos Gauguin art public domain