The Sense and Nonsense of the Luddites

Luddites thrive on nostalgia and a fear of technological progress. However, before dismissing them as sentimental fools, it would be wise to examine a few of their more reasoned arguments, especially in light of the advent of artificial intelligence and its impact on the labour market.

To some, AI is but the latest iteration of the much touted ‘paperless office’, the big promise of the 1980s which never quite materialised. In fact, the world’s offices are probably inhabited by more paper shufflers than ever before.

To others, including most Luddites, artificial intelligence promises an Armageddon of job extinctions as work gets outsourced to smart machines and systems that make large cohorts of human workers redundant, or in HR-speak, superfluous to requirements.

Speaking of human resource professionals; they are likely amongst the first to be replaced. AI recruiters, already in vogue, are likely more efficient and less biased than the tone deaf experts in pointless rhetoric and hollow jargon they replace. Though it is tempting to say ‘good riddance’, before that vengeful thought is finished, your job – much more meaningful, no doubt – is next to follow the dodo into extinction.

Pity the HR Pro

AI promises a windfall in productivity and profit to its adopters. It enables corporates of all sizes to do ‘more with less’ which, after all, is the whole point of business: an unrelenting quest for efficiency.

The ascendancy of human resources as an actual profession – it used to be the domain of the director’s (now: CEO’s) secretarial pool – is largely owed to increased competition and the need this imposes to control the one variable difficult to predict or, indeed, manage: labour.

Pity then the poor HR professional caught between the often impossible demands of management and the natural animosity felt by those it attempts to manage. This rather precarious position is not to be envied. Though its elimination by AI is unlikely to cause tears to fill a valley, be careful what you wish for – and remember the ‘competency framework’ (see HR Speak Translated below).

Modern-day Luddites maintain that AI will slash more jobs than previous rounds of automation. Economists, practitioners of a particularly error-prone science, disagree and point to their beloved Luddite Fallacy as offering definitive proof that technology creates more jobs than it destroys. That argument holds water. Whilst the nature of work is subject to constant change, its volume tends to increase over time.

The advent of robot-assisted manufacturing and globalisation made countless blue collar factory workers redundant. Their jobs were either taken over by robots or moved to low wage countries such as Mexico, China, and Vietnam. However, this offshoring of jobs has now mostly stopped due to increased political volatility and risk with many corporations re-shoring work and rerouting supply chains.

Disruption ≠ Destruction

The classical political economist David Ricardo (1772-1823), ‘inventor’ of free trade, was one of the first to show that innovation does not destroy jobs. Whilst progress does cause disruption, its harmful effects on the labour market are mostly short-lived as societies adapt to new realities and explore and exploit the new opportunities it brings.

Take the British textile industry, once dominant and now virtually non-existent. The introduction in the late eighteenth century of automated power looms put many skilled and relatively well-paid workers out of a job.

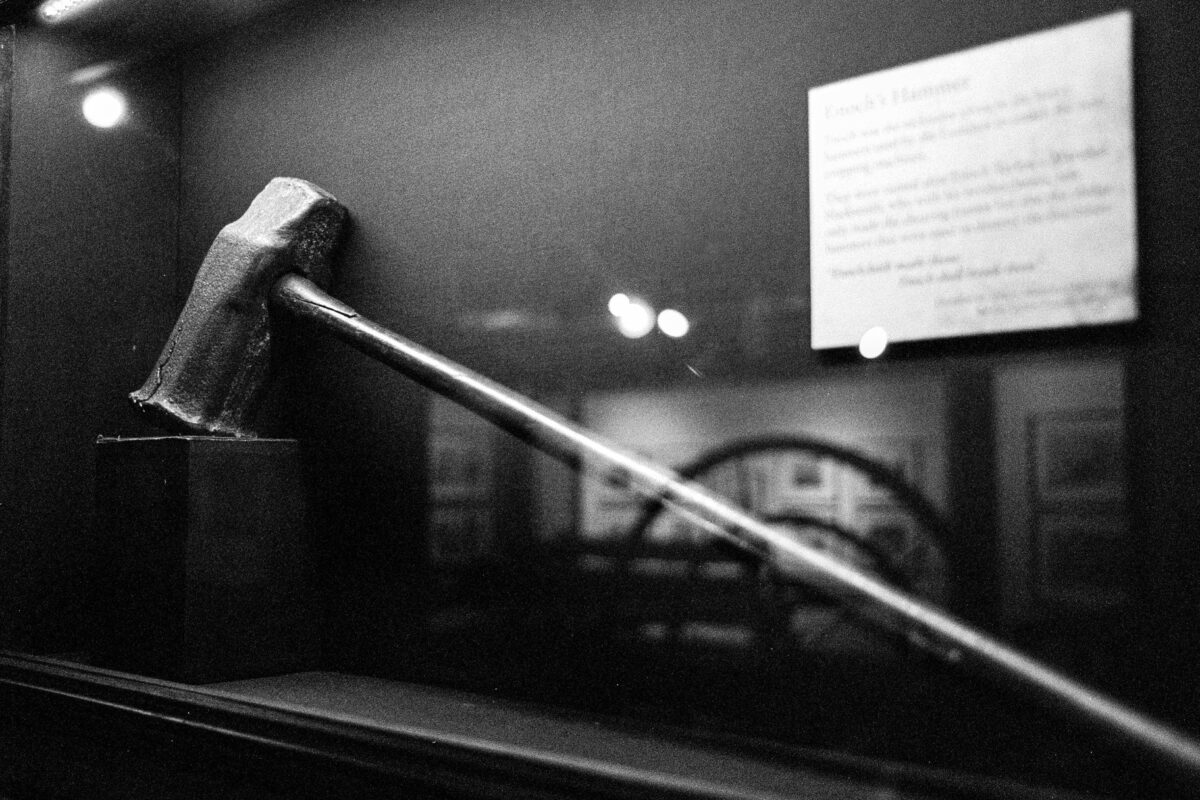

They revolted and used industrial sabotage – smashing machines – to demand progress be stopped. The uprising was sparked by the mythological Ned Ludd who took a hammer to the mechanical loom that was to undermine his livelihood. The rebellion soon got out of hand and required the army and parliament to get involved. The former employed considerable violence to protect the interests of the textile barons whilst the latter hurriedly passed a law to make ‘machine-breaking’ a capital offence. Subsequently many Luddites were hanged or transported to faraway penal colonies. In the end, both barons and workers lost and Britain’s textile industry moved elsewhere.

In a sense, Luddites are fighting the tide of history much like the apocryphal King Canute who, sitting on his seaside throne, demanded the rising tide respect his royal persona and not wet his feet or robes. The twelfth-century anecdote exposes the foolishness of those in power believing they are in control of events.

The Betamists’ Lament

The betamists of ancient Greece and the cartographers who followed in their footsteps have made way for GIS (geographic information system) engineers. Betamists measured distances by counting their steps and published the findings in books and tables. Cartographers improved on this by drawing the contours of the land and its topographical features.

Typesetters have also disappeared adding considerable joy to the life of print publishers who generally detested these highly unionised and strike-eager professionals. Telegraphists keying in morse code, one of the first new ‘tech’ professions to appear in the mid-nineteenth century, have gone as well. Even their morse code, a forerunner of the digital age, is now no longer recognised as a valid means of transmission.

Lamplighters, elevator operators, rat catchers, town criers, film projectionists, dispatch riders, milkmen, switchboard operators, wheelwrights, typists and scribes have also departed. Jobs likely to face the axe before long include tax advisors, warehouse workers, cashiers, taxi drivers, fast-food workers, sports referees, telemarketers, translators, librarians, computer programmers, proofreaders, travel agents, postal workers, consultants, etc. The list is depressingly long and also affects countless creative professions such as, say, essay writers and editors.

Growth industries where most new professions are likely to emerge include spaceflight, waste management, environmental care, climate science, cryptography, education, and anything related to the more or less meaningful pursuits undertaken in free time, of which their will be plenty if AI advocates are to be believed.

Bread & Games

In due time, artificial intelligence is supposed to upset the work/life balance with the latter gaining prominence to the detriment of the former. Futurologists predict the arrival of universal income as a way to keep the masses replaced by AI happy. If Rome has taught us anything, it is that people need bread and games to keep from running amok. Universal income can provide the bread whilst Netflix and Grand Theft Auto or Minecraft can provide the distraction.

However, the 1970s and 1980s harbour a few valuable lessons as well. The automation of offices and factories increased productivity significantly – expressed as GDP per hour worked. Annual growth rates fluctuated around the two-percent mark in both Europe and the US for much of this time. The windfall profits thus generated did not benefit the ‘surviving’ workers whose productivity increased but without the attendant rise in wages. In fact hourly compensation, properly adjusted for inflation, has largely been stagnant over the past forty years.

Using data supplied by the US Congressional Budget Office, a typical middle class family has lost well over $17,000 in (annual) purchasing power since 1979. Whereas from 1973, US productivity per hour worked has increased by a whopping 74,4%, the average hourly wage rose a paltry 9.2% (US Bureau of Statistics and Bureau of Economic Analysis).

Inequality, likely to be acerbated by AI, is growing almost exponentially with the top once percent of earners enjoying a 138% rise in compensation since the mid-1970s versus a rather meagre 15% for the bottom 90% (Social Security Administration wage statistics).

Plumbing the Future

The slow but steady erosion of purchasing power is an expression of the mismatch between capital and labour. Before they were defanged, defenestrated, discredited, and dismantled in the freewheeling 1980s and 1990s, labour unions made sure that increases in productivity (and profits) were shared more equitably – and matched to compensation.

Perhaps it goes too far to link the decrease in purchasing power to the demise of the unions as in a grand conspiracy against workers – the case for causality remains iffy and ignores the havoc wreaked by globalisation – but, coincidence or not, the fact remains that the divergence between capital and labour is unlikely to slow down anytime soon.

The expectation that universal income will provide a hedge against the possible onslaught of AI seems a pipe dream. A society that values a mediocre CEO up to four-hundred times more than it does a firefighter, educator, nurse, or police officer is unlikely to be overly generous to those caught out on the wrong side of progress.

Though the Luddite Fallacy may well hold, those worried by it would be well advised to look for jobs impervious to artificial intelligence or other major labour market upsets. Think of plumbers, beauticians, and caregivers in addition to the civil service and the military. Curiously enough, the world’s oldest professions, including the one best left unmentioned, are precisely the ones most immune to change.

| HR Speak | Plain English |

|---|---|

| Alignment | A measure of your behaviour |

| Change management | Getting desperate, need to plug holes now |

| Centralisation | We have the power and you don’t |

| Competency framework | Work hard and be nice/kind |

| Downsizing | Business is failing, you need to go |

| Employee engagement | Your level of excitement on the job |

| Employee value proposition | Productivity |

| Executive search | In the market for a bullshitter |

| Human capital management | Just makes us sound super important |

| Intellectual capital | Measure of knowledge present |

| Key performance indicators | We make and change these as we go along |

| Leverage | Our tools to make you behave |

| Outsourcing | Opting for ‘el cheapo’ |

| Paradigm | Sounds learned. We are clueless too |

| Performance appraisal | Work harder, do better |

| Redundancy | Go away |

| Remuneration | Pay |

| Retrenchment | We misjudged the market to your detriment |

| Rightsizing | Sorry, next time we’ll do better. Pinky promise |

| Strategic human resources management | How we manage you lot |

| Talent pipeline | Future supply of working stiffs |

| Training needs analysis | How to make you less dumb |

| Value add | The profit we reap from your job |

Cover photo: Enoch’s Hammer wielded by the Luddites of Yorkshire to smash automated looms. The fearsome device was named after inventor Enoch Taylor who invented and manufactured shearing frames that cut the nap (the fuzzy surface) of woollen cloth to a uniform level, robbing ‘croppers’ – highly skilled workers – of their livelihood.

Photo credits

- © 2024 Photo Enoch’s Hammer by Bastian Greshake Tzovaras

- © Public domain illustration ‘The Leader of the Luddites’