The Pinochet Legacy After 50 Years

A Coup Remembered

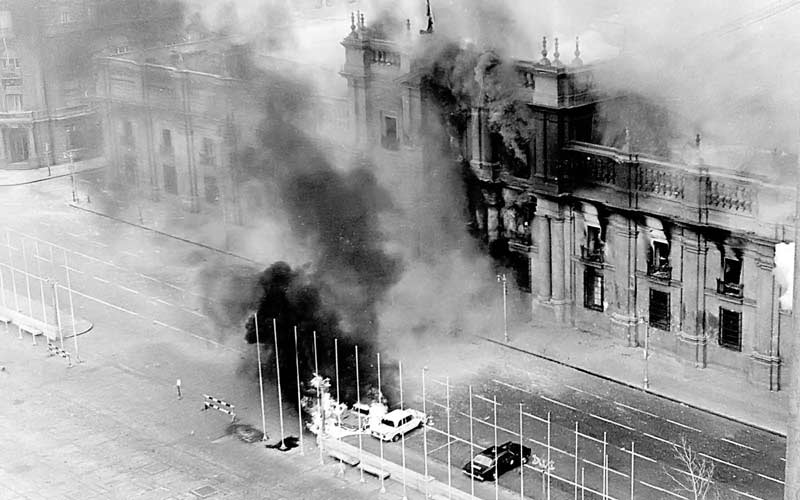

On this day fifty years ago, a pleasant early-spring Tuesday, democracy fell to armed force in Chile. Absconded in La Moneda, probably one of the least gracious buildings erected by the Spanish colonial empire, the constitutional president of the country, Salvador Allende, fought a desperate fight against putschist generals.

Plumes of smoke rose ominously from downtown Santiago as Hawker Hunter jets fired missile barrages at the palace. Inside, chaos reigned after it became clear that all army units in and around the capital had joined the uprising and the government had no supporters left.

President Allende took to the airwaves: “Soon,” he said, “the calm metal of my voice will no longer reach you. It does not matter. You will continue to hear me. I will always be beside you.” Hours later, troops assaulting the palace found the president dead in his private chambers alongside a loaded Kalashnikov – a gift from his Cuban friend Fidel Castro.

That same night, the bustling city went into quiet mourning wondering what horrors daylight would bring. A curfew kept everybody locked inside including throngs of partygoers, the fine fleur of Chilean high society, who had assembled at the majestic Hotel Carrera to celebrate the downfall and death of their president with champagne, hors d’oeuvres, and dance.

The hotel, now home to the ministry of Foreign Affairs, overlooked the smouldering rubble of La Moneda and was not a hundred meters distant from the place where President Allende met his death and/or executioner only hours before – the circumstances surrounding his demise have never been clarified.

Days and weeks of terror followed. In the aftermath of the coup, an estimated 80,000 people – including civil servants, union leaders, intellectuals, and artists – were arrested and interned at the National Stadium where some 1,200 summary executions took place and many more suffered torture. A plundering of libraries, accompanied by book burnings reminiscent of those taking place on the eve of Kristallnacht, sought to rigorously rid the country of leftist thought and influences.

The Reluctant Putschist

The military takeover was carried out, but not orchestrated, by army commander Augusto Pinochet (1943-2006) who went on to govern the country for seventeen years. Before his power grab, the general was considered a staunch constitutionalist and enjoyed the trust of the president.

Only after considerable prodding by Admiral José Merino (1915-1996), commander of the navy, did General Pinochet join the plotters. That happened just a single day before the admiral had promised to move – alone if necessary – against the president.

Whilst still a surprise, the putsch came not entirely unexpected. After President Allende set the country on a ‘peaceful road to socialism’, political unrest was never far away. The conservative newspaper El Mercurio delighted in stoking the fires of civil unrest and was duly helped along by the machinations of the Nixon Administration.

At the time, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was determined not to allow another Cuba to emerge in America’s backyard. Mr Kissinger was apparently instructed by his boss to make the Chilean economy ‘scream’ in agony. Due to the ideologically inspired but thoroughly impractical policies pursued by the Allende government, it ultimately required little to no effort to derail the local economy.

Wrecked by near-continuous strikes, armed factory takeovers, roaring inflation, and mounting debts, Chile had clearly embarked on a path to self-destruction. Alarmed at the breakdown of government and the apparent outbreak of anarchy, large swaths of society called on the army intervene and reestablish order. Soldiers out on leave reported passersby sprinkling corn kernels on the pavement to imply cowardice. The polarisation of Chilean politics and society came to a head on 11 September with a violent event that scars and polarises the nation to this day.

Although the Pinochet regime rebuilt the economy and transformed Chile into a regional powerhouse, he did so over the dead bodies of more than 3,200 of his countrymen. Untold thousands of Chileans only narrowly escaped a similar fate by fleeing into exile. General Pinochet ended the Chilean dream – a peaceful transition to socialism and an empowering of the masses – and turned it into a nightmare.

Enduring Split

Some thirty-odd years after the return of democracy (1990), and seventeen years after the general’s passing, more than a third of Chileans still express approval of the dictatorship. However, the vast majority of people condemn and deplore the violent excesses of the regime. Still, General Pinochet remains a saviour of the nation to many, including those born after his rule.

President Gabriel Boric (37), an admirer of Mr Allende, failed in his attempt to have all political parties represented in parliament agree on a joint statement of remembrance to declare that a military takeover can never be justified. Two mainstream conservative parties refused to sign and were absent from the formal presentation of the Commitment to Democracy. Javier Macay, president of the Independent Democratic Union, explained that his party doesn’t wish to be present anywhere the memory of Salvador Allende may be celebrated.

Tensions over the Pinochet Era again peaked late last month after General Hernán Chacón (86) was handed a prison sentence of 25 years for the aggravated murder and abduction of Víctor Jara, a theatre director, singer, writer, university professor, and communist activist. In the days following the coup, Mr Jara was kidnapped, tortured, and shot 44 times by a platoon of soldiers under the command of Mr Chacón. The general committed suicide moments before police arrived at his home to escort him to prison.

On Sunday, President Boris joined thousands of Chileans in a commemorative march organised by victim associations and ending at Morandé 80, the ornate entrance of La Moneda Palace through which the lifeless body of Salvador Allende was carried out, on a stretcher and wrapped in a poncho, half a century ago.

- © 2010 Photo Palacio de la Moneda by Santiagonostalgico

- © 2010 Photo Salvador Allende by Fundación GAP