The Mingling of Politics and Business

China Syndrome

What goes up doesn’t necessarily have to come down. A case in point: China. The last time the country’s GDP contracted was in 1976 (-1.57%) – the year both Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai passed away, the Cultural Revolution collapsed with the denunciation and purge of the Gang of Four, and reformer Deng Xiaoping began his improbable yet unstoppable rise to the top.

Since those hectic days, a recession in China has just implied a slower pace of growth. Last year was particularly ‘bad’ as economic activity increased by ‘only’ 2.99 per cent in the wake of enduring covid lockdowns.

Of late, market analysts and assorted China watchers have been in overdrive, predicting an imminent meltdown of the economy and suffering a China Syndrome of sorts. Absent trustworthy official data, the doomsayers are looking for telltale signs that confirm their worst fears.

They point to the weak housing market and the mounting trouble at large real estate developers such as Evergrande, Country Garden, and Sino-Ocean all reportedly facing financial difficulties, missing coupon payments, or pleading with bondholders for better terms.

No Jobs for the Young

Also, youth unemployment now reportedly stands at twenty percent. CEOs of Western companies with a presence in the country deplore the sluggish conditions and detect a pronounced and pervasive lack of confidence in the immediate future which keeps consumers from spending and businesses from investing. The spectre of deflation haunts an economy that suddenly seems to have lost its mojo.

The near universal worry about China and its predicament is understandable for a recession there would reverberate around the world. In some quarters, the language employed by China watchers has already reached a fever pitch: ‘ticking time-bomb’, ‘Lehman moment’, ‘imminent Japanification’, and ‘economic long covid’ are but a few of the more civil descriptions used to characterise the present moment lived by the country.

Observers less given to hyperbole seem equally worried. They point to President Xi Jinping’s ‘meddlesome’ rule and his apparent inability to pacify the Americans. On a four-day visit to Beijing earlier this week, US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo urged the leadership to reduce the risk of doing business and warned that American companies are beginning to see China as ‘un-investable’.

Mrs Raimondo follows in the footstep of secretary of state Antony Blinken and treasury secretary Janet Yellen who also visited Beijing recently to assure China’s leaders that the US is not ‘decoupling’ and would prefer to ‘stabilise’ relations. This is not necessarily what the view from Beijing looks like after President Joe Biden signed an executive order restricting US investment in Chinese semiconductor, quantum computing, and artificial intelligence companies.

Zero Covid, Zero Confidence

As the strict, arbitrary, and almost draconian ‘zero-covid’ policies were lifted, most analysts expected – not unreasonably – a release of pent-up demand. Forecasts had China’s GDP jump by over six per cent this year. The current target stands at ‘around’ five percent, allowing the government some wriggle room. The reality is harsher still with GDP slated to advance by just three percent – if that much.

The post-covid splurge was short-lived and petered out almost as soon as it began. The gloom visited upon the Chinese during the pandemic proved resilient. The lockdown forced consumer confidence down from a hight of 127 at the start to a low of 86 towards the end (with 100 representing the perfect equilibrium between optimists and pessimists). Moreover, consumer confidence hasn’t recovered since.

In a sign that China remains an authoritarian state where bad news calls for suppression, the National Bureau of Statistics simply stopped publishing figures on youth unemployment and consumer confidence altogether.

Foreign direct investment is down in Q2 by a staggering 87% year-on-year. The adage that the party will not bother entrepreneurs and investors if they, in turn, do not bother the party, no longer holds. Its demise under the guidance of President Jinping, who tends to micromanage the economy (and society), has introduced a disconcerting measure of uncertainty.

It can no longer be assumed that the economy will keep on growing ad infinitum. In fact, it already is on a downward trajectory in dollar terms: deflation and a weakening currency conspire to wipe trillions off the dollar value of China’s GDP. According to Goldman Sachs analysts this eventually may shrink economic output (in dollars) by up to $3 trillion.

Market watchers wonder if the Chinese are just in a temporary funk or if their economy is facing challenges of a more structural nature. A middle-income trap looms as does the inevitable reckoning with a shadow banking system running both amok and scared. In May, Xinhua Trust became the first Chinese shadow lender to file for bankruptcy. Since then, Zhongrong, the country’s largest trust, missed a number of payments.

Shadows of a Crisis Foretold

Operating largely outside the control and scrutiny of the People’s Bank of China, notwithstanding a 2020 clampdown on off-book lending, trust companies took in almost $2.7 trillion (RMB 21 trillion) from mostly retail investors lured by annual returns often in excess of ten percent. About a third of those deposits found their way, directly or indirectly, to the now ailing real estate sector. Another sizeable chunk was loaned to local governments which are struggling to repay their debt (amounting to an estimated RMB 57 trillion / $7.2 trillion).

Investors are understandably spooked by the opaque triad of trusts, property developers, and local governments. However, most cannot withdraw their cash since trust products usually carry terms that inhibit or prohibit early redemptions. Those conditions may yet help China to avert a banking crisis – if it starts to address the problems in earnest.

The trust issue, of course, fails to promote or sustain consumer confidence. However, experience in China and elsewhere shows that consumers are a fickle lot and can, almost literally, turn on a dime. It is therefore up to President Jinping to show that he is – albeit belatedly – committed to the pursuit of high growth and willing to undergo some self-restraint. The trouble is, of course, that not even President Jinping can prove that he will not change his mind yet again. He now seems stuck in a web of his own making.

Yes Men

The president has repeatedly signalled his willingness to sacrifice accelerated growth for ‘quality growth’ which must prepare the country for a sustained economic (and even military) dispute/conflict with the US. National greatness, security, and resilience are the priorities. This implies that business and politics are no longer separate and must merge towards a common end – however ill-defined and subject to the whims of the Great Helmsman.

Just like way back when, in a past better not mentioned, policy errors accumulate: the sudden cancellation of the zero-covid policy exposed the fallibility of President Jinping. The crackdown on tech firms scared off entrepreneurs and stifled innovation. The central bank’s timid response to deflation – its rather inexplicable refusal to cut interest rates significantly – hampers economic growth and dampens consumer demand. In the administration, technocrats are being overruled by party loyalists and dogmatists.

A storm of near perfection appears to be gathering. The present short-term issues coincide with unsettling long-term trends such as an ageing population and mounting Western opposition to unbridled expansionism and the transfer – voluntary or otherwise – of intellectual property. As the country embarked on its remarkable ascendancy almost fifty years ago, China proved that democracy and an open society are not preconditions for fast growth and rapid development. Now it starts to find out that centralised authoritarianism may in fact prove detrimental to continued growth.

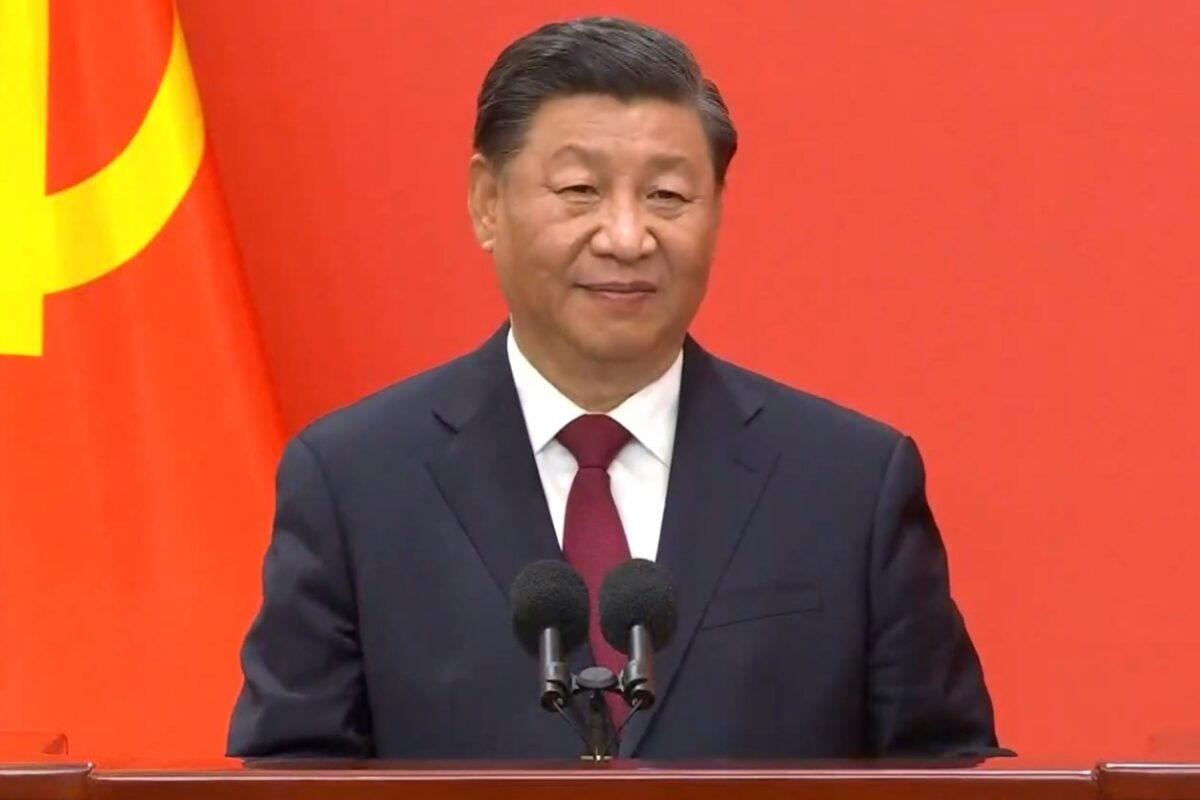

Cover photo: President Xi Jinping of China.

© 2022 Photo by China News Service