S&M: When Adam Met Karl

Flaws in Economic Theory Exposed

Standing on the cusp of the fourth industrial revolution which promises to fuse the physical, biological, and virtual (digital) worlds, the capitalism that Karl Marx dissected and analysed seems to be running out of steam – at least in its present form. Though corporate earnings reach into the stratosphere, Adam Smith had already observed in the eighteenth century that the ‘rate of profit is always highest in the countries which are going fastest to ruin’.

The bedrock that sustains Marx’ core thesis is as valid today as it was in Victorian Britain: capitalism is driven by a divisive class struggle in which the ruling-class minority appropriates the surplus labour of the working-class majority as profit. Countless economists, philosophers, and political scientists, including liberal hawks, cannot find fault in the assertion that, left to its own devices, capitalism displays a self-destructive streak from which it needs protection in order to survive and prosper.

It is, of course, at this precise point that opinion sharply diverges: how to frame capitalism – as the natural state of affairs that has governed the economic behaviour of humans since the dawn of time – and ensure that its power to generate wealth benefits society as a whole.

The inequities of the present economic model have led to a staggering level of inequality that sees just eight men owning a volume of assets equal to the combined possessions of the 3.6 billion people who represent the poorest half of humanity (Oxfam, 2017).

Last year, the world’s billionaires added $762 billion to their collective worth, enough to eradicate global extreme poverty seven times over. Some 82% of all wealth created in 2017 ended up in the pockets of the top one-percenters whilst none of it went to the poorest half of the world’s population. Karl Marx would have something to say about that, as would, btw, Adam Smith.

Whilst Marx utterly failed to offer concrete answers and trace a path out of the capitalist quandary, he did manage to point out, document, and reason the system’s many inner contradictions. He also shone an unflattering light on the capitalism’s inability – at least in its unaltered and undiluted form – to provide a decent standard of living to all.

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx rallies against the bourgeoisie which he accuses of consistently demeaning work formerly considered honourable: “It has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage labourers.”

As the fourth industrial revolution takes shapes, these words gain a renewed currency. Take the plight of physicians who, before long, will undoubtedly be replaced by computers crunching big data and leveraging the awesome power of artificial intelligence to produce spot-on diagnoses. The job security of surgeons is also moving onto shaky ground as robotics take over to perform surgical procedures with a delicacy and precision no human hand, however, skilled, can match. Thus, another honourable profession is ‘de-skilled’, adding yet another layer to the division of labour.

No More Mr Nice Guy

Whilst in the German capital, where he had arrived in the autumn of 1836 to study Law at the University of Berlin, Marx slowly fell under the spell of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) who proposed a reform of the state along rational liberal lines – at the time a revolutionary notion and a dangerous thought. His enthusiastic espousal of Hegelian philosophy did, however, not go unnoticed and blocked his chosen career path as a professor.

Liberals were most certainly not welcome in German academia. Far from deterred, Marx almost instantly turned to writing. He rejected the idealism of both Immanuel Kant and Johann Gottlieb Fichte, much in vogue during the first half of the nineteenth century, which holds, broadly, that reality can be inferred through reasoning.

Marx would have none of this and concluded that reality – i.e. the material world – ultimately guides all thinking. This also meant the expulsion of the divine from all thought processes. Going a few steps beyond Hegel’s rational liberal state, Marx concluded that, absent God, there was no need for a state at all – a crucial detail that was clearly overlooked by the ideologues who founded the communist states that proliferated in the last century.

It was not for a lack of trying, but Marx never quite became the philosopher he aspired to be. Instead, he turned into a formidable critic of whatever phenomenon caught his attention – peerless in his ability to remove the clutter and get to the crux of the matter. Later in life, Marx cultivated a profound dislike of philosophy, concluding that the point is not interpret the world, but to change it by exposing its shortcomings via ‘critique’.

Thus it is that today’s many agents and drivers of change, from Black Lives Matter to the #metoo and LGBT/OK2BME movements, owe a debt of gratitude to Marx who recognised that every society adopts the mores of its ruling class. Hence, nothing can change unless these rules, values, and customs have been thoroughly uprooted – rebuilding the very foundations upon which society rests.

The concept, rescued from oblivion every other generation or so, that relations between people should shape the world and determine its direction, as opposed to relations between capital, was already suggested by Marx over 150 years ago. Yet, since then we haven’t actually moved an inch closer to that ideal for the concept is at odds with the numbers that drive and underpin progress.

After all, most decisions by corporates, individuals, and governments are made to create or increase profits, or benefits. Marx understood this, as did his opponents on the other side of the argument. The difference resides in Marx’s anger that such decisions usually lead to further oppression and exploitation. It helps explain why eminent British historian Eric Hobsbawm (1917-2012) remained a committed Marxist throughout his life, notwithstanding the unequivocal failure of states and societies organised on Marxist premises: “I side with the poor and oppressed and cannot do otherwise.”

Archimedes Questioned

Even if, as happens in modern liberal societies, all boats rise on the incoming tide of prosperity, some enjoy much better buoyancy than others as evidenced by the extremely lopsided division of capitalism’s spoils.

What Marx got patently wrong was his assumption that, once properly organised and enlightened, the disadvantaged classes would rise up and overthrow the system; paving the way, by doing so, to a veritable nirvana. Prodded into action by leaders of dubious moral quality, the masses did what was expected of them only to discover that some pigs, and their canine helpers, are more equal than others and demand deference to their newfound station in the grand revolutionary order of things – and more food too.

“Somehow it seemed as though the farm had grown richer without making the animals themselves any richer – except, of course, for the pigs and the dogs.”

From Animal Farm by George Orwell

Though Marx pinpointed the contradictions inherent in capitalism, he failed to offer a firm and workable alternative. In a peculiar twist of fate, Marx may, in fact, have become one of those philosophers he disliked: an analyst par excellence but not a revolutionary driving change. Whilst it may indeed be true that human beings will never truly be free until capitalism has been dismantled, so far no one has managed to do just that and build a free society on the system’s dying embers.

Yet, after languishing in limbo for more than a decade following the decline and fall of the Soviet Union, Karl Marx has become fashionable again – even in the United States where, according to a 2017 poll, about half of those under thirty reject capitalism. Though socialism remains a taboo word almost as bad as ‘liberal’, a growing number of young Americans are quite fed up with a system that they consider rigged against them.

Adjusted for inflation, the median household income in the US has stagnated since 1967 for the bottom sixty percent of the population, yet corporate profits have soared since the 1960s. Most businesses no longer funnel the lion’s share of their profit back into the business, preferring to save or return the money to shareholders as dividends – hurting productivity and depressing wages.

In one of his more prescient moments, Marx foresaw this. He predicted that the logic of capitalism would, over the course of time, result in rising inequality, chronic unemployment and underemployment, stagnant wages, the dominance of large powerful firms, and the creation of an entrenched elite whose power would act as a barrier to social progress. Eventually, the combined weight of these problems would spark a general crisis, ending in revolution.

In 2016, the first generation of Americans expected to be less well off than their parents, hovered between two anti-establishment candidates – Bernie Sanders on the left and Donald Trump on the right – who both claimed to end business-as-usual, albeit from opposed angles. Just as Trump triumphed against most pundits’ expectations, so may a progressive candidate down the electoral line. A revolution can take many shapes and need not necessarily be a violent affair.

The prospect is less farfetched than conservatives – and Fox News – tend to believe. It would by no means be the first time that US voters swing to the (far) left in an attempt to rebalance political and economic power. The New Deal with which the administration of Franklin D Roosevelt slashed the power of big business in the 1930s would have carried Marx’s wholehearted approval. Moreover, Roosevelt’s policies represented a sustained effort to regulate unbridled capitalism and position the state as the starter motor of the economy and the final arbiter on the distribution of the wealth produced.

It is rather too easy to ascribe the utter failure of communism to the emergence of a new upper class that may not have possessed the means of production in a legal sense, but controlled it all the same. Likewise, the failure of ‘pure’ capitalism is not to be blamed solely on the billionaires the system brings forth – tempting though that explanation may be.

Enter Mr Smith

Whereas Karl Marx carefully mapped capitalist contradictions but failed to offer an alternative, his supposed ideological nemesis Adam Smith (1723-1790), on whose intellectual legacy he built his own thesis, has a number of suggestions worth examining. Smith is, of course, the hero of libertarians, fiscal conservatives, economic freebooters, and laissez faire ideologues the world over.

Just as with Marx, he is but little understood – and quite often misunderstood. The two books that, arguably, have set the outer limits of economic science (if there even is such a thing) – Das Kapital: A Critique of Political Economy and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations – have been quoted often but seldom read.

Perhaps the most important of myths surrounding Adam Smith is that the Scottish economist and philosopher advocated for free markets, unencumbered by state rules and regulations and guided by the ‘invisible hand’ of self-interest that steers individuals gently towards behaviour that benefits all of society. That is simply not what Smith wrote, proposed, or supported.

Smith was keenly aware of the asymmetries of information and power, and of the problems surrounding rent extraction. He also expressed concern that, left to do as they please, capitalists would just appropriate value – a nifty shortcut – rather than create it.

Smith moreover argued that properly framed and competitive markets would result in low profits and high wages – indicative of a healthy economy. A supporter of progressive taxation, Smith was no free marketeer.

Margaret Thatcher, rather clueless, thought otherwise and reportedly carried a copy of the Wealth of Nations in her handbag. Entrusting the UK economy to Smith’s invisible hand and – much more importantly – financing her national restructuring exercise with the unexpected proceeds of the North Sea oil bonanza, Thatcher went after short-term results, running down the welfare state and promising better lives for all as power was devolved to the individual.

Middle-income liberals went merrily along with the neoconservatives in a political conspiracy that now, three decades later, has run its course to end, predictably enough, in a deregulated gig economy that fails to provide a living wage to its growing legion of ‘de-skilled’ participants.

Adam Smith lived at a time when the First Industrial Revolution was picking up steam and people started questioning the authority of the church. A product of the Scottish Enlightenment, Smith and his intellectual sparring partner David Hume considered the many upsides to the profound and rapid changes taking place around them.

Though a strong advocate of free markets, Smith also showed concern for the excesses that could result from an absence of regulatory oversight. In his lesser-known work The Theory of Moral Sentiments, the Scottish philosopher starts out by noting that self-interest also includes altruism: “However selfish man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it.”

The Price of Everything

Smith argued that due to the intrinsic value unlocked by the division of labour, it is the sole determinant of price – and the only true source of economic growth. He conceded that wages, profit, and rent complicate matters in more advanced societies. By splitting complex jobs in a large number of small components – the sum of which produces the end product – Smith argued that labour, through specialisation, would power a considerably increase in productivity, generating additional wealth in the process.

This is, of course, what drove the industrial revolution. The surplus resulting from the division of labour could be used, Smith argued, to develop and install more labour-saving machinery, driving down prices in an almost virtuous circle.

Adam Smith also showed considerable interest in the diamond-water paradox, which had already been touched upon by Plato in one of his dialogues. The paradox asks why water, essential to life, represents little to no value whilst diamonds, which lack practical applications, are considered very valuable. Distinguishing between use value and exchange value, Smith concluded that the real price of anything is determined by the ‘toil and trouble of acquiring it’. Decoupling price from usefulness was one of Smith’s greatest accomplishments.

Of course, in economic life prices are set according to marginal utility principles that discard both labour and usefulness as determinants. Instead, the price of any product is derived from its importance to the owner.

Austrian economist Eugen Böhm von Bawerk (1851-1914), one of the founding fathers of the Austrian School of Economics and a fierce critic of Marx though not very impressed by Smith either, illustrated the concept of marginalism by recounting the considerations of a farmer who possesses five sacks of grain: the first sack is required for sustenance, the second offers a nutritious food supplement to ensure strength and good health, the third sack feeds his poultry, the fourth one provides for distilled spirits, and the fifth and final sack – having no practical use and thus the one with the least marginal value – is fed to wild birds that merely amuse the farmer.

The first sack of grain – providing sustenance – is the most valuable of all. The farmer could lose four sacks and survive. However, losing his last sack of grain would mean hunger and death.

Considering the origins and determinants of value, Marx took another more complex approach: ‘socially necessary labour time’ which includes the entire labour input – i.e. the sum of the division of labour (skilled and specialised workers) – needed to turn out the desired product. It also considers the total quantity of labour needed to produce a commodity in a ‘given state of society under the prevalent social conditions’.

Thus, to Marx, price is set by social rather than individual conditions. Hence, technological breakthroughs such as those taking place during industrial revolutions lower the price of commodities and increase both productivity and competitiveness. This puts less advanced societies at a distinct disadvantage which they are unable to overcome. Marx’ philosophical tack helps explain colonialism and, to a modest extent, inequality.

Laggards and Losers

What Marx is saying, in his usual roundabout way, is that technological progress likely produces a class of laggards and losers. Hardly a revolutionary assertion, and perhaps even an open door, the insight finds a contemporary application as a vast number of professions will probably be wiped out over the next few decades thanks to technological advances.

In and of itself this need not be a cause of worry: entire professions have disappeared (been ‘de-skilled’) before without major long-term societal consequences. In fact, as the world changes, so do the jobs that make it go round.

However, taking Smith’s division of labour to its logical conclusion implies that skilled jobs would be disassembled into ever more tinier components which then may be performed either by unskilled labour or robots. In this scenario, highly-paid skilled labour is but an intermediate phase in a process of productive deconstruction that must, invariably, lead to lower wages and unemployment, negating the very benefits to society Smith sought to achieve via the division of labour.

Smith, the humanist, would surely have objected to this outcome. Where his libertarian acolytes go wrong is when they hail Adam Smith as a champion of free market absolutism. He was a much more nuanced thinker than that. In fact, on a number of crucial points Smith and Marx were in full agreement: both would have been horrified, albeit for different reasons, at the present crony capitalism which consistently neglects the public interest and, in business, decouples merit from reward.

Inconvenient Truth

When politics no longer matters and market forces shape the world, masses tend to become restless – after a while. Already in 2007, then-chairman of the US Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan remarked that the outcome of the following year’s presidential election did not matter: “We are fortunate that, thanks to globalisation, policy decisions in the US have largely been replaced by market forces. National security aside, it hardly makes a difference who will be the next president. The world is governed by market forces.”

Greenspan’s observation was a particularly astute one. Little noted at the time, the chairman’s words harboured the most inconvenient of truths: until the financial crash of 2008, economic considerations set the policies of government in most industrialised nations. The grand national visions of yore were ruthlessly and recklessly brushed aside as the body politic became the body pragmatic: Thatcher, Reagan, and others transformed the Me Decade into a frenzy of consumerism – collectivism was out, individualism in.

Neither Smith nor Marx had foreseen such a development. Both thinkers considered a healthy and vibrant society the source of all economic and individual virtue. However, the empowering of the individual necessitated a retreat of the state which also left a vacuum for business to claim as its own.

Privatisation and deregulation were duly called for and remain fashionable concepts and essential ingredients of any neoliberal economic setup. Atomised, just as Smith’s and Marx’s de-skilled workers, private individuals soon discovered that they had traded their political say on the altar of the millionaires who soon became billionaires.

When the house of cards erected in the early 1980s crashed in 2008, voters began to rebel. In Europe and North America, demagogues of various stripes soon promised a return to old values, blaming others – preferably foreigners – for whatever societal ill, imaginary or otherwise, identified as the culprit or agent of unwanted change.

This trend culminated in the election of Donald Trump to the White House and the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom. In continental Europe, populists came to within a whisker of power.

What Would Adam Say?

Adam Smith distrusted large corporations and monopolies. He also argued that a well-paid worker is a more productive one and argued in The Theory of Moral Sentiments that ‘social intervention’ is required when the free market is unable to provide a living wage.

Smith also surmised that whilst education is of value to the individual, it is so to society as well. The Scottish thinker was well ahead of his time in recognising that some goods, such as education, are ‘non-rival’ in nature: their consumption by one individual does not reduce the availability to others.

Markets are often unable to provide such ‘non-rival’ goods for these do not conform to classic supply and demand models. In fact, Smith presents quite a list of public goods that should be collectively underwritten, including national and individual defence (military and police), justice, education, and services ‘that support commerce in general’ (infrastructure).

Smith also had clear ideas on how to finance these essential public services: via taxes levied in proportion to the ‘revenue enjoyed under the protection of the state’. Apple, Amazon and other big tech companies, please take note.

Smith’s world was one technological eons distant from the present. However, the core of the message contained in The Wealth of Nations remains as true now as it was then. Yet, Smith is also misunderstood and his thoughts have been misappropriated by neoconservatives and neoliberals to justify the dismantlement of the state apparatus – not as a way to increase governmental efficiency or spend tax revenue more wisely, but for ideological reasons.

What Would Karl Say?

Told you so!

Marx’ convoluted solutions, notwithstanding their verbose presentation, offer little practical support to present-day economists. However, his insights in the formation, application, and other more nefarious uses of capital priceless.

Looking for a Blueprint

With the Fourth Industrial Revolution now well under way, what is an economist to make of a future in which the demand for skilled labour declines sharply and wealth concentrates into ever fewer pockets.

The first thing to consider is that economics, whilst hugely important, is but one aspect of society and should therefore not enjoy primacy over politics. Bill Clinton could not have been more wrong when he exclaimed during the 1992 election campaign: “It’s the economy, stupid!” His remark was, however, a sign of the times.

Public interest, as a broad all-encompassing concept, has been largely ignored for over a quarter century as the debate focussed on cutting budgets, bridging fiscal deficits, and promoting industry. As a result, Donald Trump was awarded the US presidency by disgruntled voters who, in Great Britain, heaped all blame for their predicament – underpaid, underhoused, undereducated, and up to their eyeballs in debt – on the European Union.

Now that the genie of popular ire is out of the bottle, putting it back in will prove quite the challenge. Smith and Marx are no help either. Instead of rejecting the much-maligned experts, voters may want to point their arrows at those politicians who insist that business-as-usual is the only way forward.

Keep calm and carry on is, however, not a long-term option. Western societies must take back control of their own destinies, not by erecting barriers to trade or angrily leaving supranational bodies such as the European Union, but by returning to the pragmatic approach that produced their prosperity in the first place: an acknowledgement that free markets do not exist for good reason: the law of the jungle just isn’t compatible with civilisation.

Hence, markets need guidance from society via its politics as an expression of honest popular will – not the one cynically manipulated by demagogues. Excessive riches, accumulated whilst enjoying the protection of the state as Smith would have noted, need curtailing whilst at the other end of the scale, extreme poverty must be eliminated.

There used to be a system that accomplished these twin objectives quite well and produced vast riches for those nations that embraced it. Social democracy – a peculiar blend of Smith and Marx with a few other great thinkers thrown in for good measure – used to be the only game in Europe and to a somewhat lesser extent in North America.

Glorious Years

During three decades that Keynesian state management of demand held sway and delivered the impossible combination of high growth, low inflation, and full employment – an era celebrated in France as the Trente Glorieuses (the glorious thirty years, 1945-1975) – social democracy was seen as a formidable bulwark against the lure of communism.

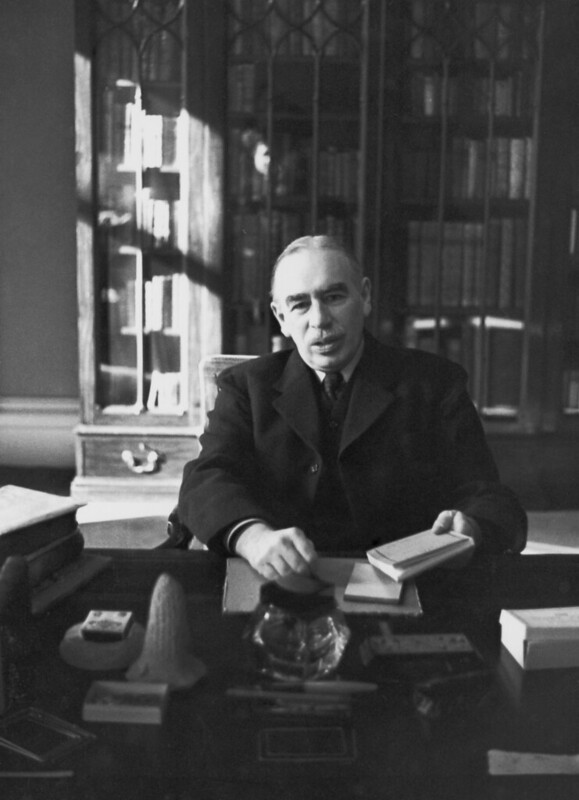

Marxism was deemed disproved and irrelevant as Europe followed the model carefully plotted by British economist John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) which delivered the best of both worlds without descending into either tyranny or anarchy.

Yet, in the latter half of the 1970s cracks began to appear. Economists wondered if lagging corporate profits might not be boosted by deregulation, curbing inflation, and weakening the power of labour. The previous entente between business, government, and labour was considered outdated and no longer fit for purpose.

In Europe, one country after the other started prioritising monetary policy, awarding independence to central banks and ditching the fiscally loose policies of the Keynesian model. The changes did manage to increase corporate competitiveness and profitability. It also decoupled productivity from wages, particularly in the United States where between 1973 and 2013, productivity increased by almost 75% whilst real wages rose by less than 10% over the same period – and not even 1% for those dwelling at or near the bottom of the income scale.

The demise of social democracy was long in the making and finally sealed by Prime Minister Tony Blair in the UK and Chancellor Gerhard Schröder in Germany, both of whom promised renewal – an only vaguely defined ‘third way’ – but merely pushed their parties to the right, making them indistinguishable from the more conservative movements whose mantras they adopted as their own.

Why, then, not vote for the real thing? After voters caught on, they deserted social democratic parties in droves and, by doing so, vacated the political centre ground. In the UK, voters may now chose between a Conservative Party hijacked by its combative, irrational, and nationalist fringe and a Labour Party likewise in the grip of extremists. Some choice. Elsewhere on the continent, a similar, though perhaps slightly less radical, polarisation of politics has taken place.

Instead of focussing on finding contemporary applications for the teachings left, and insights offered by Adam Smith, Karl Marx, and other great thinkers from a more distant past, it may be worthwhile to look at recent history and see what may be salvaged from Keynes.

He, after all, accomplished what all learned minds thought quite impossible: delivering economic growth sustained over a long period of time with full employment, rising wages, and declining inequality – all in an environment that kept inflation within manageable range and acknowledged the primacy of politics over economics.

Social democracy has drawbacks as well: it is rather boring and slow-moving, and because of that, not particularly good at producing fireworks. Social democracies are also reluctant to celebrate the individual and, as such, would not produce good reality TV either – nothing much to gape at in awe or horror.

In fact, not much to see but people going about their business, relatively free, prosperous, secure, and reasonably concerned for the well-being of others – and deriving a modest degree of pleasure from that: an essential ingredient of a happy life as Adam Smith noted.

Cover photo: Adam Smith (left) and Karl Marx had more in common than is often thought.

- © 2011 Photo of John Maynard Keynes by Patrick Chartrain

- © 2016 Photo of Margaret Thatcher by Picryl

- Other photos public domain