Seldom Down, Never Out

Pedro Sánchez

Echoes of the Franco Era still haunt Spain in subtle and often divisive ways. Now, a vibrant democracy, the country has taken decades to shed its past and rid society of the last vestiges and symbols of authoritarianism. A watershed moment was reached when Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez ordered the remains of dictator Francisco Franco moved from a vast mausoleum to a more modest grave.

Though the Franco family challenged the reburial in court, the exhumation went ahead as planned with the coffin carried out of the grand basilica in the Valley of the Fallen by the dictator’s descendants and on to a helicopter for transport to a chapel at the Madrid Mingorrubio cemetery. In a clear sign of the unease still sparked by the Franco legacy, the family were not allowed to drape the coffin with the national flag. Instead, they carried the flag used at the dictator’s 1975 funeral in an act of quiet protest.

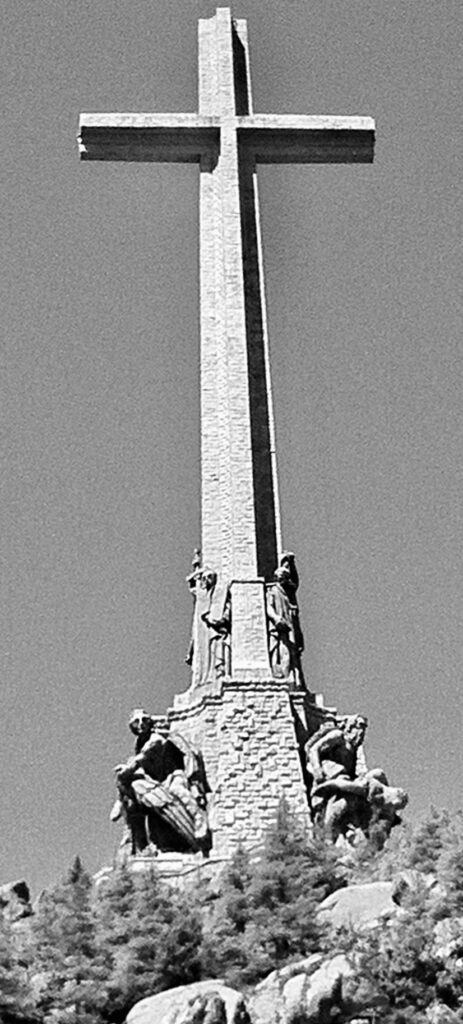

It took considerable political audacity for Prime Minister Sánchez to order the removal of Franco’s remains from the Valley of the Fallen – about 50 kms northwest of Madrid. Here, a vast, and to many unsightly, mausoleum was carved out of a rockface with the help of prison labour. The complex, including an underground basilica that rivals in size the St Peter’s in Rome, is overlooked by a 150-meter-high cross – reportedly the tallest in such structure the world. An adjacent Benedictine abbey houses the priests who say perpetual mass for the peace of those fallen during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39).

An estimated 30,000 fighters from both sides of the war are buried here. The site has been a focal point for Franco supporters and a shrine of the extremist right. Prime Minister Sánchez expressed hope that the Valley may now become a place of remembrance for all victims of the civil war.

Naturally Daring

Prime Minister Sánchez (51) is not shy when circumstance calls for daring. With the odds stacked against him and his socialist party (PSOE – Partido Socialista Obrero Español), he narrowly ‘won’ the November 2019 election, securing just 120 out of the 350 congressional seats, but keeping ahead of all other parties. The meagre result did not stop the PSOE-leader from teaming up with his main rival on the left Podemos (35 seats) to form a minority government with the implicit blessing of the Catalan Republicans (13 seats).

At the time, few in Spain would have placed a bet on the longevity of the Sánchez II cabinet. After all, his first stint at the head of a minority government lasted only 272 days and tripped over the 2019 budget for which he failed to obtain congressional approval. The proverbial comeback kid of Spanish politics, Mr Sánchez may be downed but never defeated.

In 2016, he was almost summarily removed as party secretary general by PSOE grandees – amongst them iconic former prime minister Felipe González and the Andalusian socialist leader Susana Díaz – after he failed to impress the need to form a centre-of-left coalition with newcomer Podemos. Just a year earlier, Ms Díaz had managed to distance the PSOE from the communist-dominated United Left (Izquierda Unida), breaking a bond established in the early days of Spain’s transition to democracy. She was not about to make the same mistake twice and preferred the party to plot its own course.

However, Mr Sánchez promptly put in a new bid for party leadership and in the 2017 primaries managed to edge out both Ms Díaz and another contender, thus reclaiming his old position. Whilst this power struggle was unfolding, Ms Díaz had navigated the party into the curious and unnatural position of tacitly supporting the minority government of Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy of the centre-right Popular Party (Partido Popular).

After Ms Díaz’ ouster, Mr Sánchez reluctantly agreed to uphold the deal until Prime Minister Rajoy became embroiled in a hugely embarrassing corruption scandal that rocked the nation to the core and sparked the first-ever vote of no confidence against a Spanish prime minister since the country’s return to democracy.

Upsetting the Apple Cart

From 1982 to 2015, Spain’s political landscape was clear, flat, and easy to understand and navigate. Two parties, one on each side of the ideological divide, dominated the landscape and regularly swapped places in government. There was no need for messy or awkward coalitions since either one could invariably claim an absolute majority in parliament. The scenery began to change in the wake of the 2008/9 financial crisis which hit Spain harder than most countries.

Populist agglomerations on the left – such as the Indignados Movement that grew out of the massive anti-austerity protests which erupted on May 15, 2011 – quickly capitalised on the wave of discontent and coalesced into Podemos (We Can). The new party claimed the slice of the progressive political spectrum abandoned by the PSOE and caused a major upset in the 2015 general election when the list it headed (an agglomeration of smaller and often single-issue parties) obtained almost 21% of the popular vote and secured 69 congressional seats. Podemos has since formalised a grand coalition on the left with Izquierda Unida, previously spurned by the PSOE, to form Unida Podemos.

The rise of the populist left was mirrored almost to perfection on the right with the ascendancy of Ciudadanos, a liberal right-of-centre party with Barcelona origins. Occupying the political space forfeited by the Partido Popular, severely wounded after its implication in several corruption scandals, Ciudadanos became the fourth-largest party in the country after the 2015 general election and debuted in congress with 40 seats. The party briefly supported Pedro Sánchez in a failed bid to form a government.

Since then, Ciudadanos has moved a bit more to the right bumping into the ‘great disrepute’ conservative politics suffer for historical reasons – and losing at the polls as a result. Its attempts at becoming a catch-all big tent party, along the lines of the British Tories or, indeed, Spain’s own Partido Popular in its heyday, have largely failed. In the 2019 election, Ciudadanos secured just 7% of the vote – the worst result ever for the party and good for only ten seats in congress.

Minding the Pitfalls

Prime Minister Sánchez has so far managed to deftly navigate the fractured political landscape and keep his PSOE in the driver’s seat. He exudes an unmistakeable air of statesmanlike strength, vigour, and firmness, much more than perhaps justified by his rickety coalition and with partners that excel in quarrelling. Nonetheless, his government is now likely to serve its full term. Late last year, he even managed to get a budget approved on time – almost unheard of in Spain.

However, political realities have forced the prime minister into compromises that have infuriated many of his supporters. The most controversial of these involved scrapping the archaic law of sedition, untouched since its introduction in 1822. The move was imposed on the government by the pro-independence Catalan Republican Left (Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya) on which the prime minister’s minority government relies for support in congress. The law has been replaced with one that includes the more innocuous-sounding charge of ‘aggravated public disorder’.

Mr Sánchez justifies his conciliatory approach to Catalonian independence by pointing out that tensions have eased considerably: “The main task of any leader is to build coexistence and that’s what we’re doing.” In mid-2021, Prime Minister Sánchez surprised friend and foe by announcing partial pardons for nine separatist leaders jailed for their role in the organisation of an irregular and unlawful independence referendum. They had been found guilty of crimes ranging from sedition to the misuse of public funds and convicted to serve prison terms between nine and thirteen years.

By ordering the release of the separatists, Mr Sánchez took a remarkable risk. A poll taken just before he announced his decision showed that 61% of Spaniards opposed clemency with just 29% of respondents espousing a more lenient view. However, just two weeks later that sentiment had started to change with just a slim and shrinking majority still against the pardon.

Former regional president Carles Puigdemont, who organised the rushed independence drive, was not eligible for a pardon since he remains in self-imposed exile in Belgium and has not been tried. He dismissed Mr Sánchez’ actions as ‘showboating’ and branded the pardons as ‘personal, not political, solutions’.

Mr Puigdemont’s Together for Catalonia party has since fallen out with the Catalan Republican Left, adding significantly to the loss of pro-independence momentum. The latest polls show a razor-thin, almost Brexit-like, majority of voters opposed to independence. Prime Minister Sánchez’ tactic seems to bear more fruit than the gung-ho attitude of his predecessor Mariano Rajoy who threw the book at the separatists, inflaming passions on both sides – a particularly dangerous thing to do in Spain given the country’s past.

Only Yes Is Yes

Another, and perhaps more prosaic, row erupted over the Podemos-inspired sexual consent law, aka the ‘only-yes-is-yes’ law meant to combat the proclivity of Spanish courts to hand rapists only light sentences when the victim fails to prove she strongly resisted her attackers. However, due to a reordering of criminal offence categories, the law had the exact opposite effect to the one intended. Since only-yes-is-yes came into force, those convicted of sex crimes have seen their sentences reduced considerably, leading to howls of indignation from conservatives.

Vox, a party far to the right of the Partido Popular, has been particularly vociferous in its criticism of the Sánchez II government. The party consistently seeks to paint the prime minister and his government as a cabal of leftist loons intend on destroying everything presumably precious about Spain. Returning the courtesy, the left dismisses Vox as a band of ‘fachas’ (fascists) – a very grave insult in a country where many keep personal memories alive of Francisco Franco and a few still confess to missing the caudillo.

Legacy Enchilada

To deal with the Franco legacy, a political hot potato if not enchilada, Prime Minister Sánchez was determined to push his signature Democratic Memory law through both houses of congress. The senate passed the legislation by the smallest of margins late last year. The law aims to bring ‘justice, reparation, and dignity’ to the victims of the civil war and the dictatorship that followed.

The law bans groups that glorify the Franco regime whilst it – almost paradoxically – also encourages a ‘shared discussion based on the defence of peace, pluralism, and human rights’. As such, it builds on the 2007 Historical Memory law introduced by José Zapatero, another socialist prime minister. Then as now, the Partido Popular strongly opposed the initiative as a possible prelude to the undermining of the 1977 amnesty law and the Pact of Forgetting which helped usher in democracy.

The PP’s business-like leader Alberto Nuñez Feijóo has promised to repeal the law if he wins next year’s general election. The PP has a clear issue with the past and the need to forget it. Mariano Rajoy – prime minister between 2011 and 2018 – was especially proud of cutting the historical memory budget to zero during his administration. Former firebrand PP leader Pablo Casado said Prime Minister Sánchez’ Democratic Memory law would only dig up ‘old grudges’.

As for digging up, a lot of that is being done all over the country to locate and identify the remains of tens of thousands of people who still lie in unmarked graves. This February, forensic experts in Catalonia recovered and identified the remains of Cipriano Martos, a young activist and trade unionist who died in police custody in 1973 after being forced to drink a mixture of petrol and sulphuric acid – touted by officers as a truth serum – during an interrogation.

Extremes such as the fate that befell the young Mr Martos help explain why forgetting is particularly hard in Spain. Pundits often mention the ‘two Spains’ that are destined to never meet – and remain at odds. The two countries are, thankfully, not visible on the street or audible in conversation but do shape and poison the political matrix. That subtly toxic undertone has turned many away from politics altogether. In the European Union, Spain scores lowest when it comes to trust in political parties (8%) and government (22%) according to a recent Euobarometer poll.

Low Esteem

Collectively, the Spanish are also prone to light depression. Whilst most people on the outside consider the sun-drenched, beach-lined, and culture-laden country one of the best places to live or vacation anywhere in the world, the Spanish seldom tire of complaining about their inept rulers, the byzantine bureaucracy they erected, and the chronic underperformance of the economy.

Often, Spaniards will wonder out loud what half a century or so of democracy has brought them, leaving out the bits about the tripling of the average income, social and individual freedoms unthinkable before, and joining the European mainstream at long last.

The Spanish economy is still, by some measures, a laggard in Europe. Early last year, The Economist ranked Spain last on a post-pandemic recovery list of 23 countries. However, the pessimism this may have inspired was misplaced. This year, Spain moved into fourth place on that list. The performance boost was largely due to the country’s energy mix which excludes Russian natural gas.

Post-covid, tourists began to return and helped push up GDP growth to an impressive 5.5% in both 2021 and 2022 – undoing the damage wrought by the pandemic in 2020 when the Spanish economy shrank by a staggering 11.3%. The International Monetary Fund expects the economy to keep growing, albeit at a much-reduced pace of 1.1%, this year. However, that would still beat the IMF forecast for the Eurozone.

Inflation remains steady and hovers around the 6%-mark – also lower than many of the country’s EU peers. Meanwhile, the stock market is booming with the Ibex barrelling ahead, gaining just over 14% in January and February, and reaching its highest level since February 2020 – the month before the pandemic burst onto the global scene. Banks have put in an especially remarkable performance with Santander, CaixaBank, and Sabadell all registering gains deep into double digit territory and announcing record dividend pay outs – notwithstanding the 4.8% windfall tax introduced late last year on the banks’ income from interest and commissions.

Happy Coincidences

With the economy performing better than expected, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez is ready to face down his detractors in the upcoming municipal elections (May), widely considered a rehearsal for the general elections scheduled to take place in December.

The opposition argues that regardless international comparisons, things are objectively bad with almost no wage growth and huge price increases of staples such as olive oil (+40%), sugar (+50%), and non-alcoholic beverages (+15%). Food inflation, long a thorn in the government’s side, runs at an estimated 15% even after a €700m cut in VAT on basic items.

Economy minister Nadia Calviño blames the slow release of the €77 billion in grants the country received under the EU’s pandemic recovery programme. Though the funds have been paid by Brussels, spending has been held up because of Spain’s highly decentralised form of government. With each of the seventeen autonomous regions having their own bureaucracies, it takes time for support funds to reach the intended beneficiaries.

Minister Calviño expects that most of the red tape involving the distribution of EU cash will have been dealt with during the course of the year: “That’s when we’ll see their impact.” She perhaps forgot to mention that the timing conveniently dovetails with the next general election.

Meanwhile, the Spanish tax service reports a surge in revenue unmatched by any other Eurozone member. In 2022, the tax haul hit its highest level ever, jumping 15.9 percent year-on-year and dumping an extra €30 billion into state coffers. Economic growth and inflation explain only part of the fiscal windfall. The relative generosity of the Sánchez administration, and its multiple social support initiatives, seems to offer a more likely explanation.

Good News

Finance ministry officials believe that behavioural changes in the ‘grey economy’ – the shady zone of unregistered activity – have been crucial in upping the national tax intake. During the pandemic, many people discovered that being under the fiscal radar disqualified them from receiving any form of government support. Likewise, businesses found that liquidity support was either unavailable or minimal if most of their work was kept off the books.

According to a 2018 IMF estimate, Spain’s shadow economy represented 17.2% of GDP. Pulling that significant slice out of the dark zone, if only partially, is a major accomplishment – intended or otherwise – of the Sánchez administration.

So far, the tax boost is not being deployed to reduce the government’s structural spending deficit which currently stands at around 5% of GDP – well above the temporarily suspended 3% Eurozone ceiling. In 2022, Spain’s debt-to-GDP ratio has, however, dropped markedly from a high of 118% to 113% – the steepest decline on record.

There is even so a long way to go to make up for the lavish spending during the pandemic which pushed up the debt-to-GDP ratio up by almost twenty percentage points. But Minister Calviño remains optimistic: “Despite the complex international context of the war in Ukraine, the Spanish economy is absorbing the extraordinary impact of the pandemic at an unprecedented rate.”

Chameleon

Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez possesses an undeniable knack for political survival. He is a master at picking the battles he can win whilst carefully avoiding those that he cannot. Keeping a minority government afloat with the help of a feeble and often unpredictable coalition partner is not a minor achievement. Implementing a reasonably clear and consistent set of policy initiatives under such a circumstance borders genius.

It is a given that Prime Minister Sánchez has mastered the art of compromise. However, this allows the opposition to brand him an unprincipled chameleon willing to change colours as long as he can hold on to his lofty perch. Though there may be a grain of truth to the allegation, Mr Sánchez did succeed in bringing a measure of stability to the politics Spain which was noticeably absent before.

Though polls indicate the PSOE may not win the December general election, the Partido Popular would be ill-advised to count their predicted win as a given. Mr Sánchez, the Spanish comeback kid, is unlikely to roll over and leave the stage without putting up a good fight. Moreover, the PP cannot possibly obtain an outright majority – those days are past – and has only the hard-right extremist Vox to turn to as a possible coalition partner. The return of ‘fachas’ to power is a prospect that may yet drive Spanish voters to the PSOE and Mr Sánchez in unexpected droves.

Also, and not to be underestimated, is Prime Minister Sánchez’ expert handling of the pandemic and its economic and social fallout, and the shockwaves caused by the Ukraine War. It is no exaggeration to conclude that the world has changed almost beyond recognition over the past three years with previous certainties gone and a host of new uncertainties introduced.

Spain, never known for its financial or economic resilience, and still busy absorbing and dealing with the repercussions of the 2008/9 banking crisis, was perhaps not expected to survive as well as it did – and even prosper. Prime Minister Sánchez’ extraordinary adaptability to the unexpected, and his agility in responding to crises of whatever kind, have been crucial in avoiding a meltdown and instrumental in plotting a course to a sustainable future. That legacy may well be his best asset in the upcoming election campaign – and one hard to beat.

- © 2007 Photo Valley of the Fallen by Raúl AB

- © 2014 Photo cross by Canizalesdj

- © 2023 Photo Pedro Sánchez by Partido Socialista Obrero Español