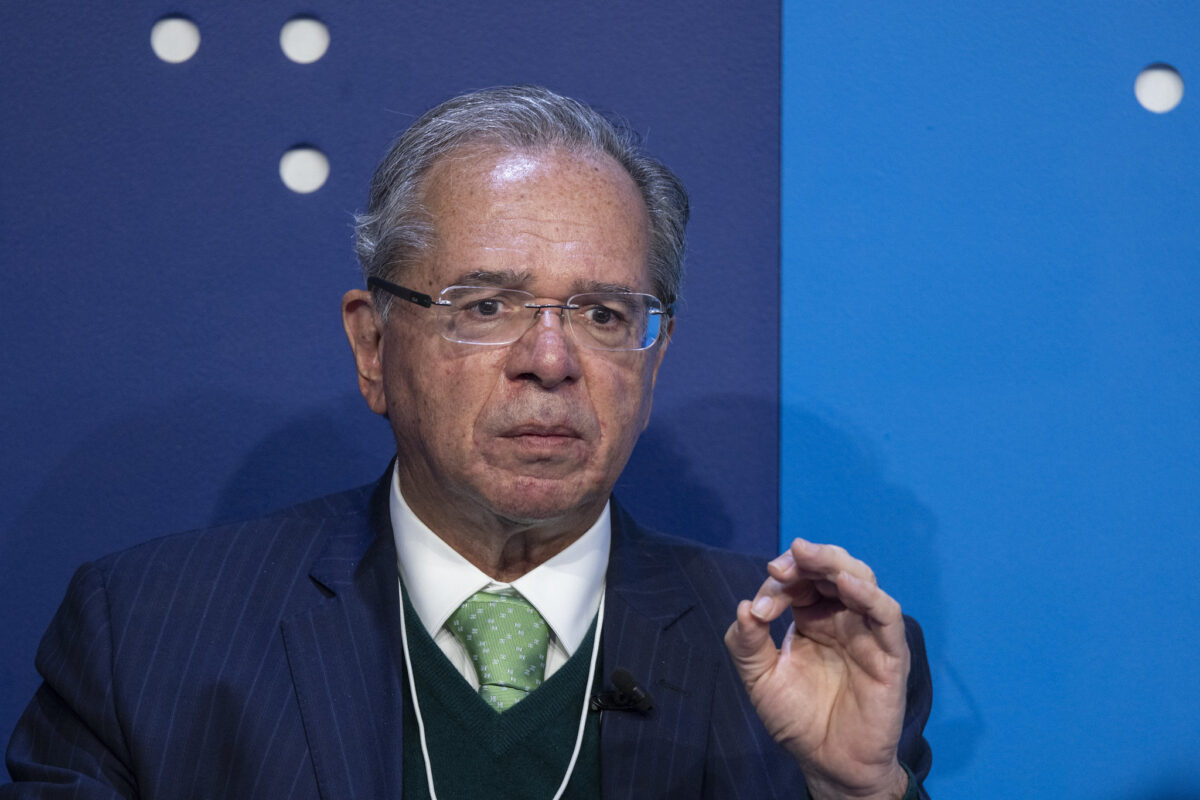

Paulo Guedes: Time for Resolve

Economic Tsar

Brazil’s all-powerful economy minister Paulo Guedes (69) looks south for inspiration. He has long mulled a Pinochet-style approach to economic management. Mr Guedes is determined to introduce a set of contemporary monetarist policies similar to those that, he says, saved Chile from bankruptcy some forty-odd years ago after a disastrous flirt with socialism – not quite unlike Brazil’s own dalliance with leftist policies.

Just as President Jair Bolsonaro, his boss, often seems enamoured of a bygone era when upright military leaders still dared step in to save the day, Minister Guedes looks longingly back to the heydays of the ‘Chicago Boys’ and their monetarism which set Chile on a path to sustained growth.

Mr Guedes should know: in the early 1980s, he held a professorship at the Universidad de Chile. However, he returned to Brazil in 1983 after seeing the monetarist policies suggested by Milton Friedman’s Chicago Boys fail spectacularly a year earlier when Chile’s economy imploded and the country’s GDP retreated by over 14% in a single twelve-month period.

Prof Friedman, winner of the 1976 Nobel memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, has since argued that the Chilean government’s decision to peg the peso to the dollar caused the massive downturn. The professor, now 97, denies ever to have suggested such a currency peg. As it happened, the overvalued local currency drove investors away and boosted consumption which resulted in a gaping current account deficit and a ballooning external debt.

Lessons and Pitfalls

Now, fully three decades later, Mr Guedes remembers both the lessons and the pitfalls: the fiscal deficit needs to be bridged and the debt brought down. Market watchers agree that with Mr Guedes at the helm, there is little chance of muddling along. There is an irascible side to Brazil economic ‘tsar’ that may well help him implement his more radical policy initiatives such as the privatisation of some – or preferably all – of the country’s 147 state enterprises. Mr Guedes repeatedly emphasises that he is unwilling to exclude any of Brazil’s crown jewels: “There are no holy cows.”

This is where the minister may clash with his boss – and , quite possibly, a few generals as well. President Bolsonaro, a dyed-in-the-wool nationalist, will not easily be persuaded to let go of iconic state-owned corporate behemoths such as oil producer Petrobras, power generator Eletrobras, and financial services provider Banco do Brasil. These companies are widely considered of strategic importance for the development of the country and sit at the core of a wider and ongoing nation-building exercise which started in the early 1960s.

Tellingly and interestingly, the seven military men with a seat in the cabinet have so far remained silent on Mr Guedes’ stated intention to shed the federal government of its prized possessions. In fact, instead of rallying to the nationalist cause, the uniformed cabinet brigade has carefully kept to the middle of the road, refusing to engage with the more politically active members of the Bolsonaro Administration.

Perhaps they are aware better than most that Mr Guedes, once obstructed, may field the most awesome of weapons at his disposal: the threat of resignation which, nearly all agree, would almost instantly send markets into a devastating tailspin. Much like the meaningful pension reform legislation he tabled, Mr Guedes’ privatisation drive seeks to re-establish the long-term fiscal equilibrium that is needed if the country is ever to embark on a path of sustained growth – as opposed to the boom-and-bust rollercoaster ride which is Brazil’s normal.

The new normal that Minister Guedes envisions includes an adherence to standards of excellence in economic governance. As – perhaps – luck would have it, President Bolsonaro is not much interested in the economy though readily admits that business needs to thrive in order for the country to grow. Rather famously, Chile’s Augusto Pinochet also admitted to a lack of interest in economic affairs and decided to ‘outsource’ the management of the economy to the University of Chicago.

Inspiring Confidence

Fully and firmly in control of the Brazilian economy, Mr Guedes inspires plenty of confidence amongst investors inside and out of the country. Since President Bolsonaro’s inauguration on January 1, the Ibovespa stock market index has jumped by about ten percent, reaching an all-time high of 98,588 early February before moderate profit-taking hit the market.

In the first days of March, markets went into a holding pattern in order to gauge the mood in congress after the government unveiled its ambitious pension reform plan. Minister Guedes insists that his initiative be approved largely as-is in order to put the country’s finances on a sustainable footing. Slowly the contours are emerging of a possible clash between President Bolsonaro, who keeps his eye on his popularity ratings, and Minister Guedes who abhors the idea of disappointing investors with a watered-down reform package that ultimately may impose social pain without much financial gain for the nation’s depleted accounts.

Ultimately, Mr Guedes wishes to emulate the Chilean experience with privately-managed pension funds providing depth and liquidity to the local capital market, thus enabling these to domestically generate the resources needed for sustained growth. Minister Guedes repeatedly points out that during almost thirty years, the Chilean economy expanded at an average annual rate bordering six percent. This awarded the country a per capita income nearly twice as high as Brazil’s. According to Mr Guedes, Chile’s success in creating a domestic source of investment capital proved the single-most important contributing factor to the remarkable growth of its economy.

Whilst Mr Guedes’ proposed solutions to address Brazil multiple deficits are well reasoned and founded in a proper understanding of the country’s complex economic dynamics, congressional approval and subsequent implementation are dependent on political considerations that stretch far beyond the minister’s remit.

Some of President Bolsonaro’s core constituencies have already expressed their disappointment, if not disgust, with the approach taken by Minister Guedes and his team. A relative newcomer to Brasília’s often hectic and confusing political scene, Mr Guedes remains first and foremost a ‘technician’. A successful banker, respected professor of Economics, and widely-read columnist, Paulo Guedes is, in fact, a political neophyte.

The trouble is, of course, that solutions to Brazil’s economic woes have never been all that difficult to produce; it is rather their implementation that has proved complicated – or simply impossible. President Bolsonaro’s predecessors often decided to kick the proverbial can down the road. Mr Guedes now argues that Brazil is running out of road and congress needs to act. With the economy still fragile and growth anaemic, the minister has a point when he demands congress acquire a sense of urgency. In order to succeed, he must ram that point home – and trust his president, a veteran of congressional power politics, to find a way to get the means.

Cover photo: Brazilian economy minister Paulo Guedes in Davos.

© 2022 Photo by World Economic Forum