Jazz: The Rhapsody of Bohemians

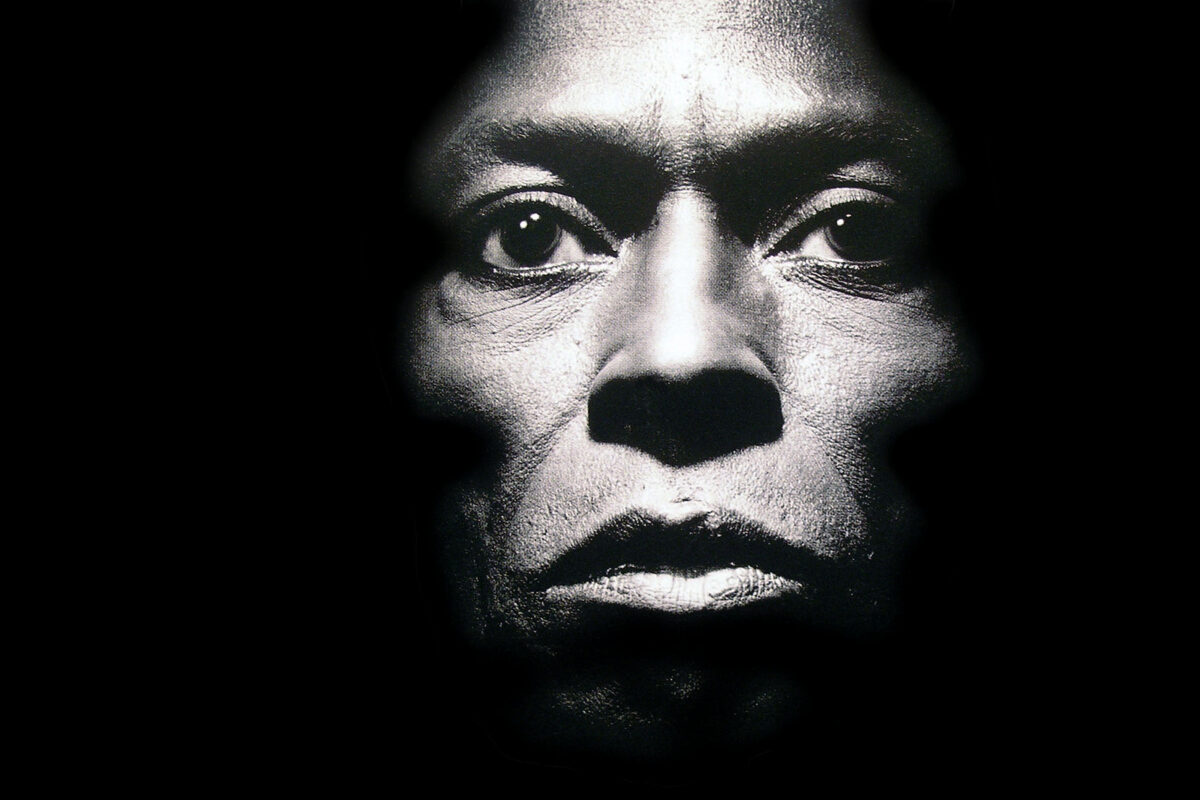

Birth of the Cool

Few music genres are so poorly appreciated or understood as jazz. To its (many) detractors, jazz is just pretentious experimentation by pseudo musicians playing, ad nauseam, the same tunes over and over again.

As seen by jazz historian Ted Gioia, the problem with jazz is that nobody has tried to explain the difference between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ jazz. Critics can – and do – argue without letup over who is the better saxophonist: John Coltrane or Charlie Parker. Then a third one comes along and throws ‘Saxophone Colossus’ Sonny Rollins into the discussion, causing mayhem to ensue.

Whilst the argument heats up, none of the critics is likely to explain what they are listening for. Cognoscenti usually agree that great jazz merges three essential elements: swing, improvisation, and originality. Each one of these key ingredients is, however, hard to define but their presence is instantly recognisable.

For an example, listen to a 1963 recording of the John Coltrane Quartet where four jazz geniuses – McCoy Tyler (piano), Elvin Jones (percussion), Jimmy Garrison (double bass), and of course John Coltrane on saxophone – offer a masterclass in swing. The track Out of this World almost magically combines multiple layers, each sovereign yet amplifying the others, into a stunningly gracious ensemble.

Swing, elusive and almost impossible to explain or pinpoint, occurs when musicians are perfectly attuned to each other without playing too many notes and – most importantly – feel when and how to play ‘behind the beat,’ ‘in front of the beat,’ or right ‘on’ it – and stretch that beat whilst keeping their timing.

For an illustrative example of beat positioning, listen to Spanish Key on the 1970 Bitches Brew double album, recently rereleased and recognised as a monument to fusion jazz and progenitor of jazz rock by the legendary Miles Davis (trumpet), Wayne Shorter (soprano saxophone), Chick Correa (electric piano), and and all-star cast.

This is decidedly not about finger-tapping rhythm or generating a monotonous pulse. In jazz, swing is perhaps best characterised as an infinite variation in cadence. In more technical terms, jazz is a harmony derived from tetrads (four-note chords) as opposed to classical music which is based on three-note chords. In other words, every chord gets an extra note in jazz often chosen intuitively to match the scale to the harmony.

All That Jazz

The Jazz Age broadly lasted from the Roaring 20s to the Depression 30s of the last century. This era not only produced liberating music but also a veritable treasure trove of exquisite and contrarian writing such as F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, James Joyce’s Ulysses, Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun also Rises, and EM Forster’s A Passage to India amongst a great many others.

The 1920s also birthed art deco which arose as a celebratory tribute to the stylishly modern and the many novelties delivered by postwar progress and prosperity: automobiles, telephones, radios, aviation, cinema. refrigeration, and many other mod cons.

However, dissenting and prescient voices already cautioned against the optimism reigning at the time and warned of a nascent dystopia with the human condition subjected to machines. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, first shown in cinemas in 1927, added a touch of gothic to menacing cubist and bauhaus visuals and delivered the (now) undisputed masterpiece of the silent-movie era.

Meanwhile, the cubism invented by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque a decade earlier, had paved the way for abstract- and neo-expressionist art defined by the likes of Edvard Munch, Erich Heckel, and Tamara de Lempicka.

For perhaps the first time in history, women found their voice and (perhaps) vocation as daring flappers: energetic and assertive young women, challenging traditional mores with exuberant lifestyles that caused great shock and outrage, and much lament in polite society. Women’s lib, and femdom, avant la lettre.

The soundtrack to these intoxicating times was provided by jazz, quintessentially American but soon the rage in Paris, Berlin, and Stockholm clubs as well. Improvisation, one of the essential traits, assured that no two jazz performances were alike. Music scores are delivered in a one-off fashion which helps explain why jazz evergreens from almost a century ago seem impervious to aging. Whilst a 60-year-old musician may play a 100-year-old composition, that performance is unique: it has never been heard before and will never be heard live again.

Cool Cats

Somewhat less hectic, and therefore more easily accessible to wider audiences, cool jazz emerged in the years following World War II as a counterweight to the soloist and wild style of bebop jazz. Rhythmically more subdued and more laid-back, cool jazz excels in understated finesse.

The style incorporates elements of classical music, leading to the ‘third stream’ offshoot that was defined by composers such as George Gershwin (Rhapsody in Blue), Aaron Copland (Jazzy), Dmitri Shostakovich (Jazz Suite No 1: III Foxtrot), and even Maurice Ravel (Piano Concerto in G Major: I Allegramente) whose appreciation of George Gershwin’s plucky jazz/classical fusion inspired the two piano concertos he composed after visiting New York in 1928.

Credited with crafting the original tonal contours of cool jazz, tenor saxophonist Lester Young (1909-1959) inspired a generation musicians – from John Coltrane to Stan Getz – who developed his free-floating introvert style into the hallmark of a second golden era for the genre, and one that still reverberates, albeit faintly, today.

Lester Young also influenced language and literature. The Beat Generation, and in particular Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, owes the musician a debt of gratitude. Idiomatic expressions such as ‘cool’ (fashionably attractive) and ‘bread’ (money) are said to have first been introduced by the hipster saxophonist from Mississippi.

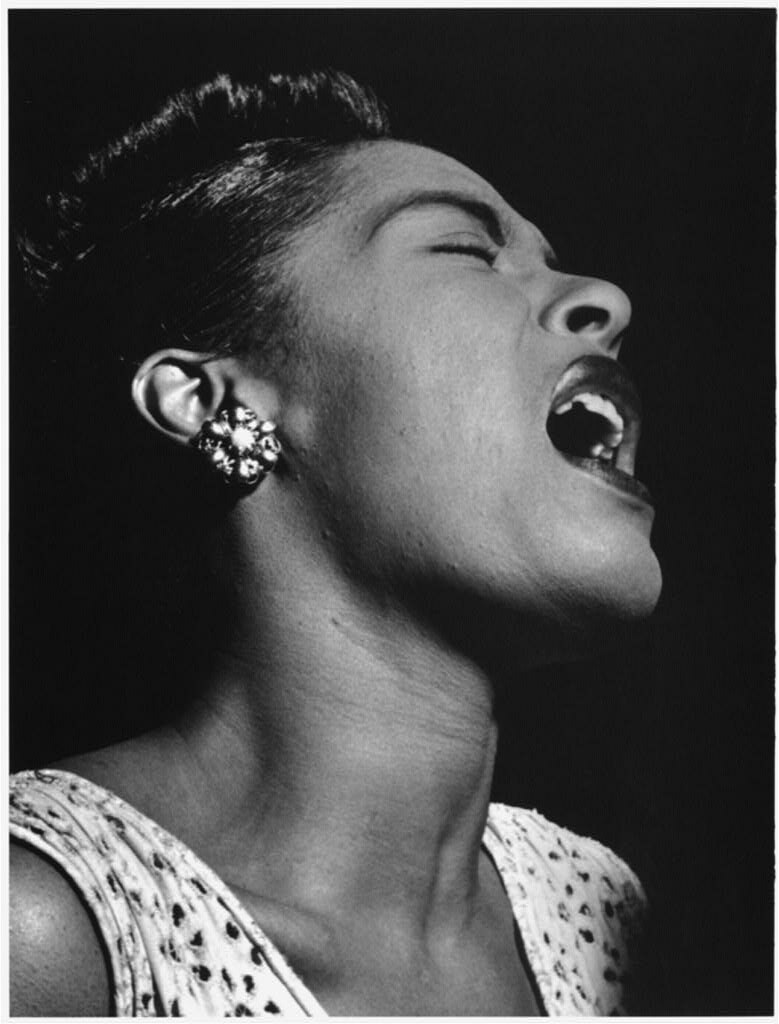

Playing with Billie Holiday, Coleman Hawkins and others on the legendary 1957 CBS television special The Sound of Jazz, Lester Young’s immortality was forged with an emotive and peerless solo performance that had the audience, producers, and technicians – literally – in tears. In the video, fast forward to minute 35:30 to be awed.

Years later, Village Voice jazz critic Nat Hentoff remembered: “During a performance of Fine and Mellow, Lester got up, and played the purest blues I have ever heard, and [he and Holiday] were looking at each other, their eyes were sort of interlocked, and she was sort of nodding and half–smiling. It was as if they were both remembering what had been – whatever that was. And in the control room we were all crying.”

Our Man in Paris

From New York, Lester Young departed for Paris where he made his final studio recording and appeared a few times on stage. However, a European tour had to be abbreviated because of Young’s heavy drinking.

On the return flight to New York Lester Young suffered an internal bleeding due to alcoholism. He died only hours after arrival. At his funeral, Bille Holiday is reported to have remarked “I’ll be the next one to go.”

Whilst the genre was invented in America, jazz became art in France. The relaxed atmosphere in Paris during the interbellum, and again in the 1940s and 1950s, drew in large numbers expat musicians, writers, painters, and assorted bohemians and socialites who converged on the city’s cabarets and jazz clubs.

To the artists of the Harlem Renaissance, the blossoming in the late 1910s of African American culture, Paris also offered relief from racial prejudice at home. Josephine Baker, Cole Porter, Coleman Hawkins, and Dexter Gordon livened up the scene-on-the-Seine with some of their best work and performances.

To this day, Paris boasts a vivacious jazz scene with countless clubs and TSF Jazz Radio, curiously enough founded (but no longer owned) by the French Communist Party, airing jazz around the clock – a rarity outside net radio.

Sophisticated Giant

Easily absorbing outside influences, and forever experimenting and adapting, jazz cannot easily be captured. Its subtle nature sets jazz apart from most, if not all, other music styles. Bridges to soul (Norah Jones, Amy Winehouse), blues (Diane Schuss, Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson), funk (Lee Ritenour, Steely Dan), and even rock (Chick Corea, Weather Report) give jazz a universality few other genres can match.

That all-inclusiveness is also one of the reasons why jazz has all but disappeared from the airwaves, confined to the esoteric and pressed into obscure niches inhabited by people who play vinyl records, read printed books, and look at art with an analytical eye – all the while feeling quite sophisticated, cultured, and – why not? – superior.

That last seemingly preposterous assertion was, in fact, borne out in a 2019 study conducted by Oxford Brookes University amongst 467 high school students and published in the journal Evolutionary Biological Sciences. The study’s lead author Elena Racevska found that students who scored highest on IQ test displayed a clear preference for classical music and jazz. Those with lower scores tended to prefer music with lyrics.

In the US, Johns Hopkins University discovered that listening to jazz can improve memory, mood, creativity, and verbal abilities. Why not give it a try with this Spotify playlist prepared by CFI Press.

- © 2010 Photo Miles Davis by Lawren

- © 2020 Photo Tamara de Lempicka by Gandalf’s Gallery

- © 2009 Photo Billie Holiday by Samkling