‘Father of the Internet’ Looking for Ways to Preserve His Work

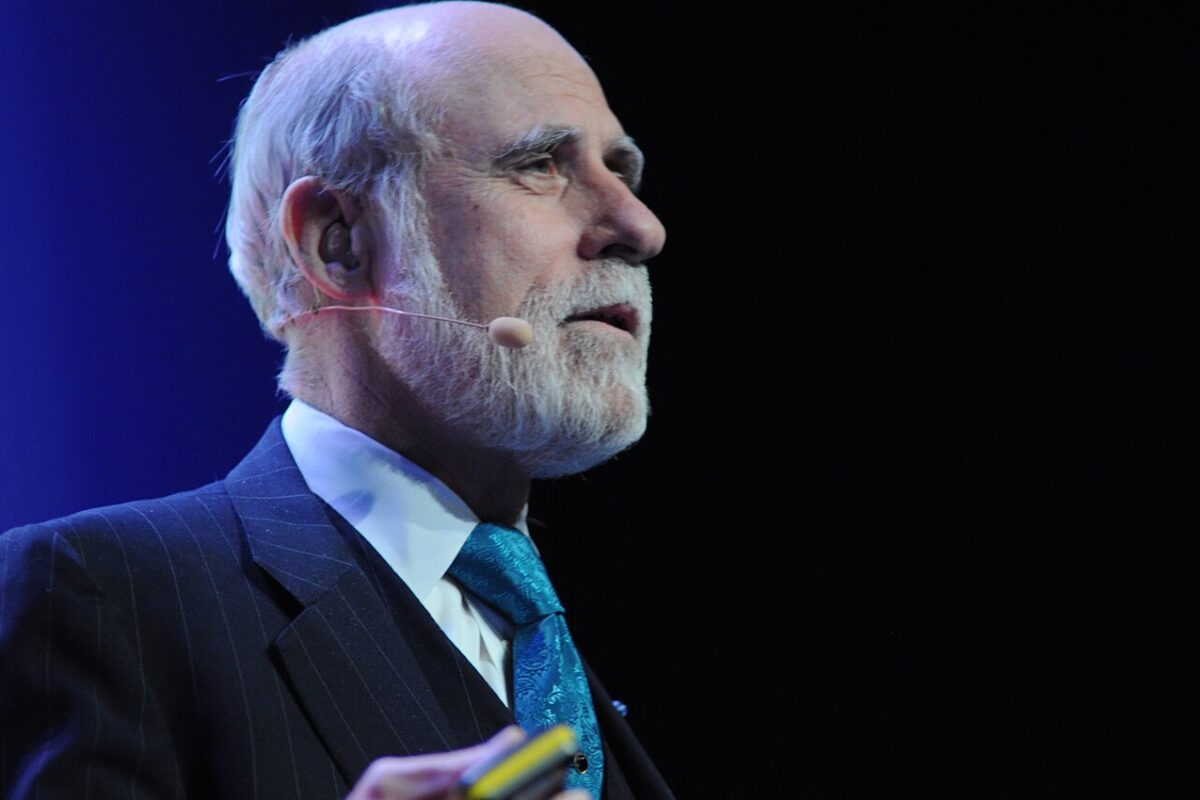

Vinton Cerf

He had absolutely no idea that his creation would be hijacked by big business, encourage tunnel vision, and spread misinformation. Vinton Cerf just wanted to build a medium that allowed for the sharing of useful information.

To that end, Mr Cerf and his colleague Bob Kahn at the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency came up with both the Internet Protocol (IP) and the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) in the early 1970s: technologies that underpin – and made possible – the internet.

In the late 1980s, Mr Cerf helped develop the first commercial email system and in the mid-1990s, he was instrumental in setting up the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), the non-profit that maintains the internet address book and provides essential coordination between regional and national internet registries.

Of late, Mr Cerf has been looking for ways to deal with the digital obsolescence, the potential loss of historically important data saved on physical media, or in digital formats, that can no longer be accessed. As both hardware and software are subject to constant change, backward compatibility is often lost, eventually rendering information inaccessible.

The issue has been known since the early 1970s but so far no solution has been found – or even proposed – that can withstand the test of time. Archivists do not usually think in years or decades, but rather in centuries and even millennia. A PDF file that is universally readable on almost any device today, may, a hundred or so years from now, be completely unusable.

That already happened with files saved by WordStar, the text editor of choice in the 1980s and which used a closed-data format that is all but inaccessible today. Physical media, such as the first 8-inch floppy disks launched by IBM in 1971 and carrying 80 kilobytes of data, can only be read by legacy equipment at specialised facilities. The popular storage solutions offered by iOmega in the 1980s and 1990s – Bernoulli Box drives and Zip, Jaz, and Clik! cartridges – have become all but inaccessible.

Black Hole

Mr Cerf has repeatedly warned that future historians looking back to the present may be faced with a black hole – a dark age from which almost no records survived: the documents, pictures, and sounds that mark our era can easily be lost as digital media are abandoned (‘abandonware’) and only fragments of data are transposed onto new carriers – a process that needs repeating ad infinitum as technological progress is unlikely to stop.

Now ‘chief internet evangelist’ at Google – possibly the world’s coolest job title – ‘Vint’ Cerf has called for the creation of a ‘digital vellum’ – a medium impervious to the onslaught of time and able to preserve abandonware, ensure its future functionality, and safeguard the accessibility of any type of file.

“We are nonchalantly throwing all of our data into what could become an information black hole without realising it. We digitise things because we think we will preserve them, but what we don’t understand is that, unless we take other steps, those digital versions may not be any better, and may even be worse, than the artefacts that we digitised.”

Mr Cerf proposes to go back to basics, pointing out that the human eye and other senses are unlikely to change noticeably: eyes can still read the stories written on clay tablets and papyrus rolls. Mr Cerf notes that future historians will not be able to find any of the correspondence between the protagonists of important events since email records will have vanished without a trace.

“Today, historians can reconstruct events by finding letters and other key documents that are kept at libraries. Important documents will probably survive, but context is often sourced from the writings left by less important actors, commentators, or witnesses. These will undoubtedly vanish.”

At Google, a company always eager to take on massive projects on a global scale, Mr Cerf may be at just the right place to help shape the digital vellum needed to preserve the present. The company has been rather secretive about its efforts to secure future accessibility to data but is reaching out to partners such as digital art collective Rhizome to develop open-source digital preservation tools. It’s a start and an initiative supported by Mr Cerf who may well father yet another internet breakthrough.

Cover photo: Vinton Cerf, the man to whom we owe the internet.

© 2009 Photo by Lift Conference Photos, Geneva