Exposing the Wage-Price Spiral Myth

Brave New World

Inflation equates thievery. It erodes the purchasing power of salaries and steals from creditors. Worse, most economists now issue dire warnings about the evils of a ‘wage-price spiral’ which is said to fuel inflation because workers demand compensation for the increased cost of living – essentially seeking to preserve the spending power of their income. This, it is argued, raises the demand for goods and services leading, in turn, to higher prices in a pernicious cycle that pushes up the price index.

The wage-price spiral is, of course, baloney.

Yet, as a macroeconomic theory it persists with few economists daring to expose the fallacy of its logic. When prices rise whilst incomes remain stagnant, demand for goods and services falls. It follows that incomes rising in tandem with prices will leave the aggregate demand for goods and services unaltered.

The ‘cost-push’ theory on the causes and consequences of inflation is part of Keynesianism, an otherwise sensible and useful set of principles. Monetary theorists with their ‘demand-pull’ explanation seem more on, well, the money. They posit that inflation originates with excess money supply, in other words: too much dough chasing too few goods.

Considering a solid decade of quantitative easing and countless other stimuli, the monetarists have a good point. According to the Atlantic Council’s Global QE Tracker, the world’s four biggest central banks1 have expanded their balance sheet by $11.3 trillion (+73%) since early 2020 to a total of some $26.7 trillion.

Central bankers are now facing a difficult balancing act: they must both end their asset purchases and raise interest rates without plunging their economies into a recession. An added complication are the uncertainties introduced by the war in Ukraine and the sanctions imposed on Russia which drive up energy and food prices. The present scenario is somewhat reminiscent of late 1973 when energy prices suddenly spiked as OPEC member states enforced an embargo on countries supportive of Israel in the Yom Kippur War.

Hot US Job Market

Then as now, most industrialised nations enjoyed a tight labour market with record low unemployment. In March, the US economy added 431,000 jobs, pushing the unemployment rate down to 3.6% – a number very close to the natural rate of unemployment – the sum of both frictional and structural unemployment with the former representing workers looking for better job opportunities and the latter comprising workers with mismatched skillsets.

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, average hourly earnings increased 5.6% year-on-year whilst there are 1.7 job openings for every unemployed person. The labour force participation rate crept up by 0.1 percentage point to 62.4% – still shy of the 63.4% recorded in February 2020 just before the Corona Pandemic hit. Analysts expect a million or more Americans to return to the labour force, possibly attracted by seemingly higher wages.

In the UK, Chancellor (of the Exchequer) Rishi Sunak welcomed the latest unemployment figures released by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) as proof of the ‘continued strength of the job market’ and emphasised the £22 billion ($28.7 billion) in cost-of-living support provided by the government to cushion the impact of rising energy and food prices.

Despite a 4.1% increase in average weekly earnings, excluding bonuses, the squeeze on living standards tightened considerably with inflation accelerating towards 8%. That headline number is, however, boosted due to the ending (in September 2021) of the corona furlough scheme which paid workers eighty percent or less of their usual pay. Stripping the statistics of this anomaly, underlying wage growth averaged only 2.7% in 2021.

Rock and Hard Place

At the British Chambers of Commerce, Chief Economist Suren Thiru warns that labour market conditions could weaken before long as a rising tax burden and inflation conspire to undermine consumer spending whilst limiting the private sector’s ability to raise wages.

Chancellor Sunak is in a particularly tight spot with the UK tax burden at its highest level since 1969 (35% of national income) and moving higher still with further funding increases planned for the National Health Service (NHS) and social care programmes. Confirming historical data and trends, the Conservative Party again put paid to the Tories’ claim to be the political home of the low-tax fiscally prudent.

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) expects the tax burden to rise to 36.2% of GDP by 2026-27 – the highest level in seventy years. With the UK national debt hovering around one hundred percent of GDP, borrowing is no longer an option. The OBR now forecasts a 2.2% drop in real disposable household incomes as of Q2 2022 – the biggest fall since record-keeping began in 1956. The cost-of-living crisis is likely to push 1.3 million people2 into poverty as energy bills for the average family hit £2,800 ($3,660) per year.

Exposing the Fake Spiral

According to former US Labor Secretary Robert Reich, since 2006 Professor of Public Policy at University of California Berkeley, there is currently no such thing as an ‘extremely tight labour market’ as suggested by US Federal Reserve Chairperson Jerome Powell.

Prof Reich points to data of the Bureau of Labor Statistics that show February’s real-term average weekly earnings lower than in the same month last year – and on par with those of 1974: “There simply is no wage-price spiral that fuels inflation. Anyone who argues that companies cannot afford to pay their workers higher wages is lacking in basic math skills.”

With corporate profits are their highest since the 1950s and share buybacks at record levels, there is plenty of cash sloshing in corporate treasuries; cash that in a truly tight labour market would flow into the pockets of workers. However, that is not happening. A survey of over a thousand US companies conducted by risk management consultant Willis Towers Watson found that firms expected average pay to rise by 3.4% in 2022 – considerably more than last year but still well below inflation. The number is unlikely to be revised upwards given the tightening of monetary policy announced by the Fed.

Economics Professor David Blanchflower of Dartmouth College, a former Bank of England policy advisor, argues that raising interest rates under these circumstanced is a ‘mistake’ likely to kill off any sign of nominal wage growth: “There is no evidence that companies are raising prices because of wage pressures.”

Instead of making salaried workers pay for the peccadilloes of central bankers and others that contributed to the present bout of inflation, decision makers may want to consider relaxing on climate panic-induced deficit spending and creating conditions that enable the rebuilding or rerouting of damaged or plugged supply lines. There are low-hanging fruits aplenty waiting to be plucked apart from cheating workers (and creditors) out of their rightful due.

Footnotes

- US Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan, European Central Bank, Bank of England.

- According to numbers from the Resolution Foundation think tank.

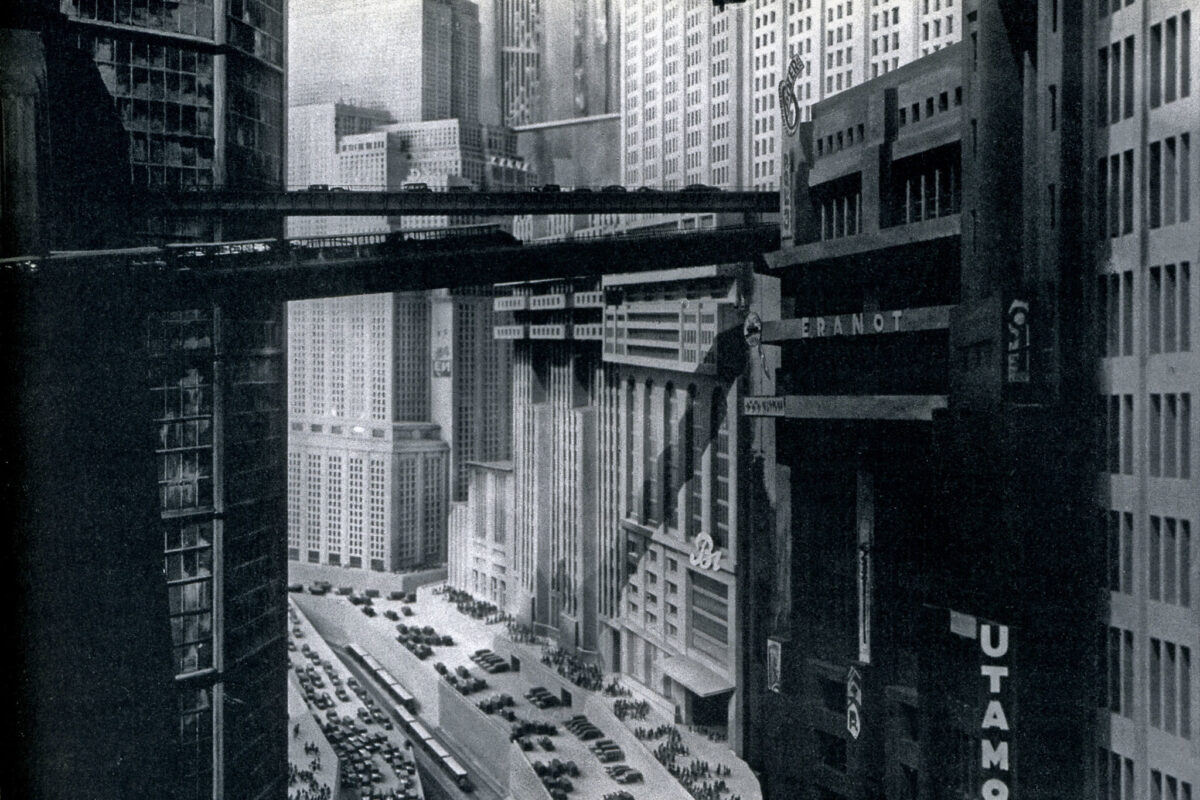

Cover photo: A scene from the 1927 film Metropolis, a dystopian masterpiece by German director Fritz Lang.

© 2011 Photo Prof Reich by Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Ethics