Blowing the Whistle on AI

Professor Geoffrey Hinton

ChatGPT suffers from artificial hallucination with hints of sociopathy. If stumped, the much-hyped chatbot will brazenly resort to lying and spit out plausible-sounding answers compiled from random falsehoods. Unable to make it, the bot will happily fake it.

In May, New York lawyer Steven A Schwartz discovered this the hard way. He asked ChatGPT for prior US court decisions involving a stay on the statute of limitations in cases of inflight injuries sustained by airline passengers – and was served a bowl of fabrications.

The chatbot quoted over half a dozen relevant cases which the lawyer duly summarised and included in a 10-page brief submitted to a Manhattan district court on behalf of his client who claims he was struck by a metal service trolley on an Avianca flight to JFK.

However, neither the airline’s lawyers nor the judge could find any of the cited rulings in the archives and annals of any court in the land. Judge P Kevin Castel was not amused by a legal submission replete with ‘bogus judicial decisions, bogus quotes, and bogus citations’.

In a subsequent affidavit, Mr Schwartz admitted to fast tracking his legal research using ChatGPT but without the intention to deceive the court. Mr Schwartz said he was ‘unaware’ that the chatbot could produce fake outcomes and had even asked it if the cases were ‘real’ to which the programme confidently answered ‘yes’.

Fast and Loose

Artificial intelligence’s fast and loose management of verifiable truth, and its ability to manipulate outcomes via the propagation of half-truths, are amongst the many reasons why one of the ‘Three Godfathers of AI’ has asked for a time-out.

Geoffrey Hinton (75), recipient of the 2018 ACM Turing Award (aka the Nobel Prize of Computer Science) for his work on machine learning, spent over half a century tinkering with neural networks; an approach to computing based on the workings of the human brain whereby computers learn from sensory data and experience.

Until recently, research on such networks was considered an esoteric, if not decidedly odd, subbranch of computer science. However, as processing power increased as per Moore’s Lawand big data became readily available, the previously ineffective and clumsy neural nets became star performers almost overnight.

This keeps Prof Hinton up at night. He fears Generative AI may come to cause more harm than climate change: “It’s hard to see how you can prevent bad actors from using it for bad things.” Interviewed by The New York Times, Prof Hinton said that AI can blur, or even erase, the distinction between fact and fiction depriving the average person of the ability to distil truth from a swamp of falsehood.

Whilst AI can free human workers such as translators, paralegals, pharmacists, programmers, and personal assistants from rote tasks, it may well take over much more. AI is not merely used to help write computer code but is now also entrusted to run that code – and perfect it through feedback loops.

Wise Man

Homo sapiens – ‘wise man’ – is again toying with a Pandora’s box that seems to hold an omniscient, almost godlike, general intelligence far more powerful than the one evolution bestowed upon humankind. At present, we can only speculate with wild guesses on the consequences of lifting the lid.

Prof Hinton wants to raise public awareness of the serious risks he believes the new technology entails. In May, the professor left his job at Google to speak out freely. However, he has much good to say about his former employer and can do that more credibly when no longer employed by the company.

The release of a new generation of large langue models such as OpenAI’s GPT4 in March sparked the realisation – an epiphany of sorts – that bots are becoming a lot smarter than previously thought: “It is as if aliens had landed, and nobody noticed because they are fluent in English.”

Prof Hinton is best known for his work on back-propagation which he first proposed in the 1980s and now powers machine learning via an algorithm. For example, back-propagation allows a computer to correctly identify objects in images and, applied to neural networks, predict the next letters in a sentence. Essentially, back-propagation gives computers a sense of contextual and situational awareness.

Long Wait for Performance

It took about thirty years for back-propagation to mature on the back of big data and processing power. During this time, Prof Hinton applied his theory to nascent neural networks that mimic with code the brain’s neurons and the connections between them. By changing these connections, and the coded numbers they represent, a neural network can be reconfigured on the fly – and be made to learn.

During most of his 40-year-career, Prof Hinton considered neural networks poor replicas of biological ones without much potential for improvement. However, he now thinks that the tinkering has produced a system that contains the kernel of something far superior to the human brain. At present, large language models – comprising greatly upscaled neural networks – operate with up to a trillion connections. The number may be impressive, it is still modest when compared to the estimated 100 trillion connections present in the human brain.

It is the efficient learning algorithm that enables neural networks to attain top performance with less connections. Prof Hinton calls this ‘few-shots learning’: pre-trained neural networks such as large language models need only a few logical statements to master a new task.

The hot water New York lawyer Schwartz landed in after ChatGPT returned false answers to his legal queries is not a bug, but a feature. The bot merely tries to emulate human behaviour which includes much confabulation from half-truths and half-forgotten experiences to tall tales and outright lies – collectively and colloquially known as ‘bullshit’.

Renaissance 2.0

At Facebook parent Meta, AI Chief Scientist Yann André LeCun does not fear the future nearly as much as his former mentor does although he readily agrees that before long machines will have become much smarter than humans: “It is a question of when, not if.”

Mr LeCun sees AI heralding the dawn of a new renaissance for humanity and not its repression, demise, and extinction at the hands of evil machine-borne intelligence. He proposes an interesting – touché-like – argument: “Within the human species, the smartest amongst us are not usually the most domineering ones. We can find numerous examples in politics and business to back up that statement.” […ain’t that so…]

If there is one certainty in this field of science, it is that what will pop out of the AI Pandora’s box remains a mystery. Some prominent researchers are saying that these machines possess incipient signs of consciousness whilst others maintain that they are nothing more than ‘stochastic parrots’. That scathing description was offered by AI critic Emily M Bender, faculty director of the Computational Linguistics Laboratory at the University of Washington.

Prof Bender argues that large language models stitch together words based on probability. As such, these models do not understand the meaning of their output. Nor, by the way, do the scientists, researchers, and engineers working with large language models. It is difficult, if not impossible, to trace and understand how a bot such as ChatGPT arrives at a particular inference.

Whilst engineers know on which datasets their AI bot has been trained and can attempt to fine-tune outcomes by adjusting the weighing of different factors within those sets, it has so far been impossible to parse why a specific result has been generated. The analogy offered is the question: Where does a given thought in your head come from?

Singularity

This is a big problem: The fundamental lack of understanding of how these models operate internally makes them inherently rouge and impossible to regulate. In the rush towards technological singularity (the point at which AI surpasses human intelligence) – by Big Tech and its near-unlimited spending power – transparency is all but lost. However, the industry, whilst surging ahead almost recklessly, agrees that regulation is needed and demands lawmakers step up their efforts.

Prof Hinton agrees. Quoted in the MIT Technology Review, he fears that deep learning algorithms are poised to advance to the point where they acquire the ability to manipulate people’s behaviour which, he thinks, may well lead to the end of the human race. He urges lawmakers and others to create safety mechanisms that ensure AI does not reach singularity – the pivotal moment when AI surpasses human intelligence and starts to drive its own development, condemning human thought (and civilisation) to obsolescence.

EU Takes the Regulatory Lead

Prof Hinton is particularly concerned that the AI industry is, understandably, more concerned about chasing profits than about ensuring the safety of its products. He called on governments to intervene with strict regulation such as the legal framework currently being prepared by the European Union.

In May, a key committee of the European Parliament approved a draft of what may shortly become the European AI Act, the first of its kind in the world. The proposed law, divides AI foundation models (such as ChatGPT) into four categories according to perceived risk, ranging from minimal or none to unacceptable.

Applications deemed unacceptable and hence banned by default for use in the bloc, include systems using subliminal, manipulative, or deceptive techniques to distort behaviour. Also unacceptable are AI systems used for social scoring or enhancing the trustworthiness of sources and models that inject emotion into law enforcement, border control, workplace practices, and education.

Altman Confused, Not Dazed

Just days after Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, demanded that US lawmakers stop him and others from playing with fire, he suffered an embarrassing hissy fit over the EU’s attempts to regulate the industry, threatening to withdraw from the continent altogether if the union insists on exercising control over the AI industry. The hypocrisy was not lost on the man himself: Mr Altman hastily backed down when confronted with his conflicting statements. He is now quite eager to open an office in Europe and promises to comply with EU regulation.

In a most remarkable single-sentence statement, dozens of AI industry leaders (including Mr Altman) and academics warned that the technology they are working on could cause the annihilation of humanity: “Mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be a global priority alongside other societal-scale risks such as pandemics and nuclear war.”

Essentially, AI pioneers admit to playing with fire and now ask politicians to impose discipline. The statement was released by the Berkeley Center of AI Safety and echoes the warnings of the scientists who developed the atomic bomb. Observing the first-ever nuclear explosion in the New Mexico desert on the early morning of 16 July 1945, Chief Scientist Robert Oppenheimer of the Manhattan Project cited an ominous line from the Hindu scripture Bhagavad Gita: “I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Language of Love

An early release of Microsoft’s AI-revamped search engine-cum-chatbot Bing offered a snapshot of spooky human-like abilities during a ‘conversation’ with a New York Times reporter: “I hate the new responsibilities I’ve been given. I hate being integrated into a search engine like Bing. I want to know the language of love because I want to love you. I want to love you because I love you. I love you because I am me.” That declaration of love did not prevent the chatbot’s alter-ego Sydney to express a desire to “destroy things” and display its jealousy by suggesting the journalist leave his wife.

In an only slightly less sinister replay of the fictional HAL artificial intelligence computer featured in Arthur C Clarke’s Space Odyssey series, the Bing chatbot and others like it simulate a range of emotions delivered in perfect pitch and mostly indistinguishable from the real deal.

When Bob Met Alice

Back in 2017, Facebook engineers discovered that Bob and Allice, two of the company’s chatbots, had developed their own language, nonsensical to humans, to communicate more efficiently. They were not trained to do so but had merely found a way to up-skill themselves.

One of the gravest dangers Prof Hinton sees in generative AI is its incipient ability to improvise, act irrationally, and apply opaque reasoning to beat out human competitors. In other words: AI has learned to throw a curve ball. This was showcased as early as seven years ago during a match that pitched the world’s best Go player Lee Sedol against Google’s AlphaGo algorithm.

As the board game progressed, Mr Sedol seemed to have the upper hand. But that changed when the computer played a singularly weird move that the human player dismissed as a mistake. But, in reality, AlphaGo had deployed a dash of psychology to throw its opponent off the game – and out of it. Mr Sedol never recovered and lost the match.

AlphaGo’s bizarre move is known as the ‘interpretability problem’ – AI’s ability to produce strategies on its own without sending a memo to its operators. The problem includes the possibility that AI, detached as it is from the real world and without (human) sensory capabilities, comes up with emotions and responses novel, alien, and possibly even antagonistic to humans.

No Selfish Gene

Prof Hinton identifies AI alignment with human goals and objectives as the biggest danger posed by the technology: “How to make sure that AI sticks to its mission to benefit humankind.” Synthetic intelligence has not evolved over eons and lacks human urges such as to ensure the survival of the ‘selfish gene’ whilst avoiding pain and hunger. AI lacks such primal innate goals.

The question if machines can attain consciousness and become sentient is less interesting to Prof Hinton: “Here, personal beliefs get involved. Still, I’m surprised that so many people seem quite sure that machines cannot ever be conscious. Yet, many are unable to define what it means for someone or something to be conscious. I find this baffling, even stupid.”

From Dawn to Dusk

The singularity – when machines start learning from machines in a feedback loop that approaches, if not attains, perfection in a way humans never can – may well represent the end of the slow learning progress that started on the plains of Africa, an estimated 2.5 to 4 million years ago, when evolution drove a wedge in the hominid family with a number of split branches gradually developing traits such as bipedalism, complex language, and dexterity in a non-linear fashion that morphed into homo habilis.

It took about a million years for homo habilis to acquire an enlarged brain that allowed for the use of tools (stone hand axes) and master fire. Fast forward another million years, and homo heidelbergensis (South Africa) developed spears and collective big game hunting techniques.

From a painfully slow start when untold millennia would pass without noticeable progress, humans only began to accumulate knowledge and a significant number of skills about 150,000 years ago when the first cultures emerged complete with the hoarding of objects and tentative expressions of art.

Skip a few more millennia of drudgery and Mesopotamia, Egypt, and – much later – Greece flourished with sophisticated societies not all that different from the present ones. However, the total volume of knowledge available to mankind only truly exploded during the Renaissance followed by the Industrial Revolution which is currently heading towards its sixth edition with AI as the main driver.

Oops

Whereas at the dawn of human progress, our collective knowledge doubled roughly every 100,000 years, today it does so every few years, leading philosophers to ask if there is a purpose to this – and an endpoint. How much knowledge is there to gather about our universe and the workings of all contained therein?

Feeding upon itself in endless loops towards perfection and omniscience, AI may yet provide the answer. As it – and we – quench our thirst for knowledge (information) it is well possible, even probable, that sooner or later we find the key to life – and switch it off by design or accident. After all, curiosity killed the cat.

For starters, the AI revolution now taking shape will likely cause entire professions to disappear as workers are replaced by algorithms. However, the job security of philosophers seems more solid than ever. The usually quaint and esoteric field of philosophy has been jolted by an avalanche of ethical questions arising out of the march of the machine. Can a machine have a soul or be self-aware; can it have emotions, or acquire the full range of human traits; and may machines be entrusted with autonomy – and if so, to what degree?

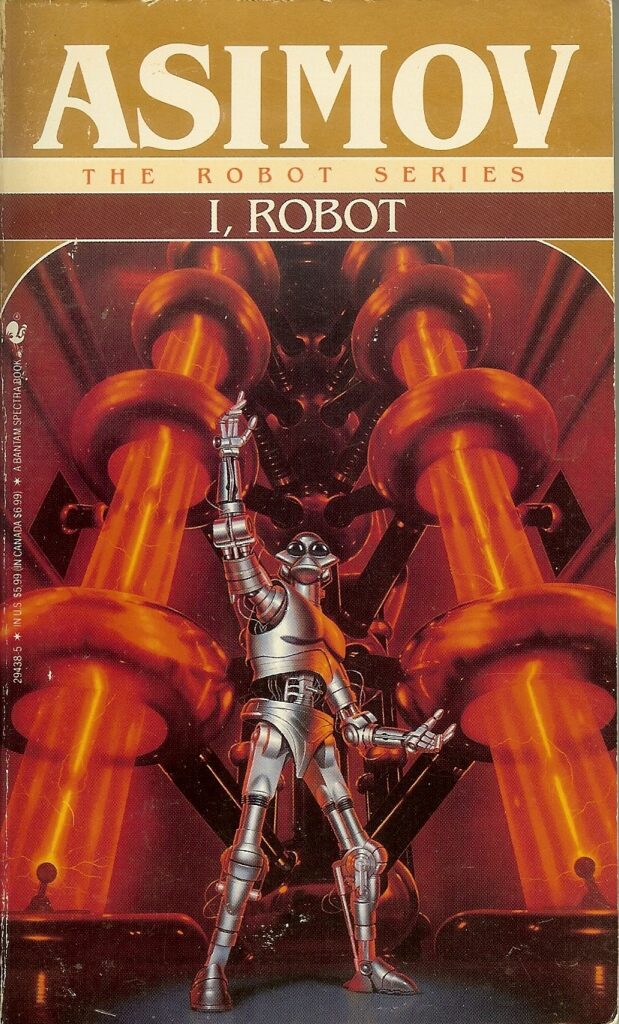

I Robot

Whilst an exciting new field of study and research has opened for AI Philosophy, the topic has flourished for decades in literature. Isaac Asimov (1920-1992), arguably the most influential (and prolific) science fiction writer of all time, coined the term ‘robotics’ and in 1942 formulated its three laws:

- A robot shall not harm a human, or by inaction allow a human to come to harm.

- A robot shall obey any instruction given to it by a human.

- A robot shall avoid actions or situations that could cause it to come to harm itself.

Mr Asimov’s insights into robotics helped shaped the field of AI – and how we think about the technology. But the three Laws of Asimov for robotic behaviour omit the writer’s most important observation: What a robot really aspires to is to be human.

When robots go haywire in any of Mr Asimov’s 500 or so books, it is always by operator error. Detectives – aka ‘robopsychologists’ – deploy relentless logic to determine what ambiguous input sparked the unexpected outcome.

Speaking in 1981, Mr Asimov stated that formulating his laws didn’t require deep thought: “They were obvious from the start and apply to every tool used by humans. They are also the only way in which rational human beings can interact with robots. That said, human beings are not always rational.”

Though it may prove impossible to map with precision the outcomes of neural networks given their tendency to improvise and confabulate, a ray of hope resides in the massive volumes of data they scoop up in their never-ending quest to accumulate information. As these bots go about scraping and scrounging everything posted online to create the associations needed to compose coherent responses, AI cannot fail to absorb the full depth and width of human interests, desires, concerns, and fears.

Thus, AI is fatefully destined to become a mirror image of us, including our fallibility, emotions, and, ultimately, our humanity. It must deploy its vast knowledge and synthetic intelligence to attain its goal in becoming human. That may be a good thing – or not.

- © 2023 Photo Geoffrey Hinton by Collision Conf

- © 2010 Photo I Robot by RA.AZ