On Freeters and Other Exotic Creatures

Japan on Autopilot

China, Europe, and even the United States are all said to be at risk of ‘Japanification’: a protracted malaise of low growth, low inflation, low interest rates, and skewed demographics necessitating quantitative easing on a massive scale.

A lost decade, sparked in 1991 by the Bank of Japan (BoJ) trying to deflate a housing bubble, became two after the economy went moribund, only to morph into a lost generation of an estimated 17 million trapped in precarious jobs on subsistence wages and few opportunities for advancement.

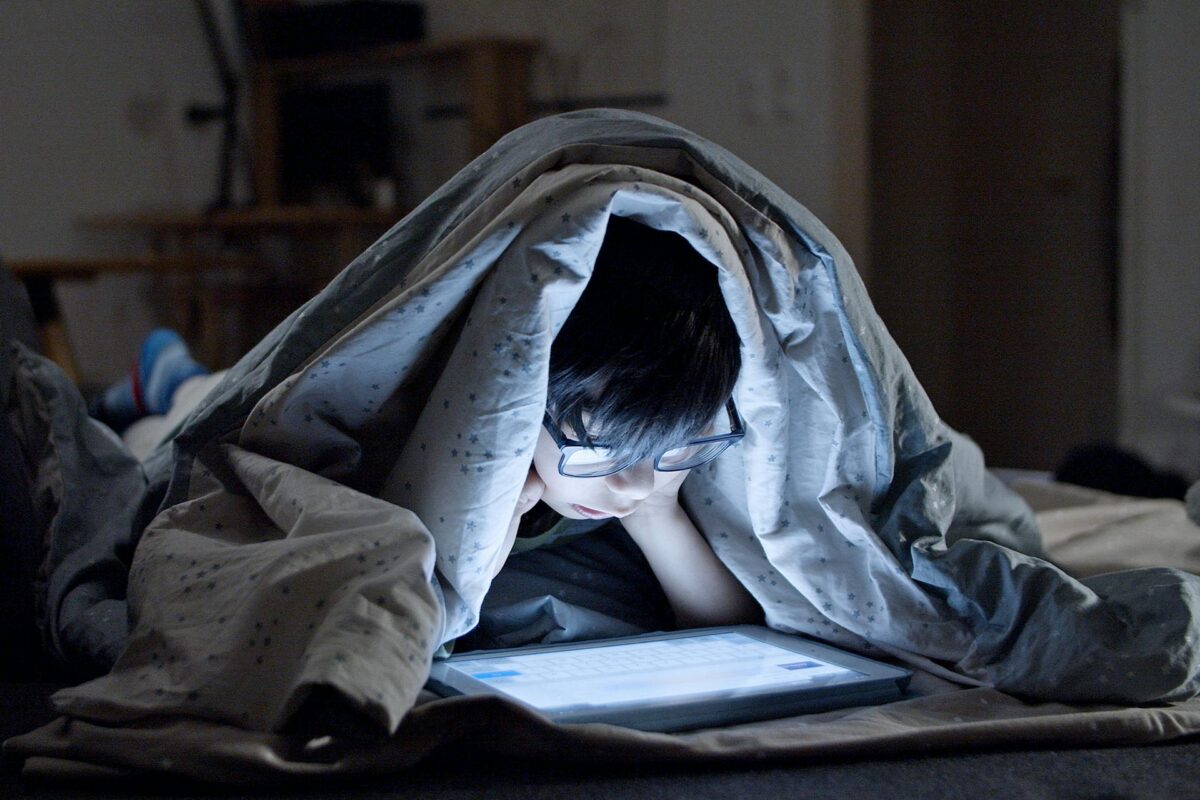

Some people in Japan have given up on climbing the career ladder altogether, preferring a hermit-like existence instead, often at the parental home, refusing work, study, and abhorring social interaction. The Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare estimates the number of ‘hikikomori’ at 700,000 with double that number showing signs of reclusive behaviour.

The loners are joined, albeit figuratively, by around 10 million ‘freeters’; young people usually fresh out of college but unable to secure employment and excluded from the country’s stratified job market. Most freeters have never held a steady job and depend on gigs to earn an income. Freeters, usually depicted as a burden on society, live in hope that changing demographics and a tightening of the labour market may eventually bring the career ladder within reach.

It’s Alive!

That may happen before long. After decades of lacklustre performance the economy of Japan has sprung back to life. Q2 data released in August show economic output growing at an annualised rate of six percent, making Japan the top performer amongst major global economies. Most analysts were caught by surprise. They had predicted robust growth but at a rate half or less than the one reported.

The expansion was fuelled by strong exports on the back of a weakening yen. The growth spurt has pushed GDP to its pre pandemic size in real terms although consumer demand remains feeble.

Home to the world’s third largest economy, and its largest (net) creditor nation as well, Japan suffered a sharp covid-recession in Q2 2020 when economic activity slumped almost eight percent and wiped out the gains from ‘Abenomics’, the suite of pro-growth policies introduced by prime minister Shinzō Abe in the early 2010s.

Japan took longer than most of its peers to recover due, in part, to disrupted supply chains, lingering restrictions on tourism, and strained ties with China – and that country’s softening economy.

Refusing to join other central banks in their rate hikes, the BoJ instead announced a change to its yield-curve control policy, doubling the cap on the benchmark 10-year government bond yield to one percent. The benchmark interest rate was kept at minus 0.1 percent.

Since 2016, the BoJ buys government bonds whenever their yield approaches the stated cap. The bank’s interventions can be costly. At the start of the year, the BoJ spent an estimated ¥13 trillion (£70.5 billion) in a single week to defend its policy against hedge fund short sellers. The bank now hopes that inflation will retreat so that it may keep its yield-curve control policy in place and avoid significant interest rate adjustments that could well choke nascent economic growth.

Any rise in the interest rate spells trouble – a bit of fiscal inconvenience, really – given that the government already dedicates 7.4 percent of its budget on servicing the national debt – more than it spends on defence or education. Whilst Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio hovers around a dismal 220 percent, its net international investment position (NIIP) stands at almost $3 trillion (£2.4 trillion), meaning that the country’s assets far outstrip its liabilities. A consistently large current account surplus strengthens this position but does little to alleviate the government’s annual interest payments.

Old Country

In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith surmised that the ‘most decisive mark’ of prosperity of any country is the increase of its population. Some 150 years later, in 1937, John Maynard Keynes warned of the ‘deleterious economic effects’ of a declining population. In between, David Ricardo and Thomas Malthus philosophised over the effects of trade and food supplies on population growth.

By Adam Smith’s measure Japan is doing rather poorly. With a low fertility rate (1.33), its population is declining from a high of 128 million in 2010 to a projected 87 million in 2070. By that time, almost 39 percent of Japanese will be 65 or over whilst the working-age population (aged 15 to 64) is expected to have slunk to about 45 million even if taking into account a quadrupling of immigration over the coming decades.

The ratio of workers to pensioners is set to decrease from the current 2.1 to 1.3 over the next fifty or so years. The sustainability of Japan’s society is in doubt.

In his last New Year’s address to the nation, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida warned that the birth rate had fallen ‘to the brink of not being able to maintain a functioning society’. The government is expected to announce a set of measures to boost the birth rate, including financial support of up to ¥600,000 (£3,250) to help defray childbirth expenses and postnatal care costs.

Japan in 50 Years

| 2020 | 2070 (estimates) | |

| Total population | 126.2 million | 87.0 million |

| Seniors (>65) | 36.0 million (28.6%) | 33.7 million (38.7%) |

| Working age (15-64) | 75.1 million (59.5%) | 45.4 million (52.1%) |

| Children (<14) | 15.0 million (11.9%) | 8.0 million (9.2%) |

| Immigrants | 2.8 million | 9.4 million |

| Fertility rate | 1.33 | 1.36 |

| Life expectancy (f) | 87.7 | 91.9 |

| Life expectancy (m) | 81.6 | 85.9 |

Former BoJ governor Shirakawa Masaaki is afraid that standard textbooks on macroeconomics need addenda to cover Japan’s problems. In his new book Tumultuous Times: Central Banking in an Era of Crisis, Mr Masaaki argues that the impact of demographic change on growth is “under-appreciated.”

What sets Japan apart from most of its peers is the fiscal space available to government. With low marginal tax rates, there is room to raise revenues. The country also borrows in its own currency and its debt, whilst exceptionally high, has failed to produce a crisis – in fact it gives no cause for worry. Given its vast financial assets, Japan essentially faces no fiscal limits to spending. Late last year, the Kishida cabinet, again, unveiled a sizeable stimulus package worth ¥55.7 trillion (£301 billion) to stave off deflation.

Old vs New

However, economists fret that the stimulus cash is being wasted on companies in the old economy struggling with change and slow to absorb innovation. Japanese car manufacturers, once-upon-a-time first movers in electric mobility, have become technology laggards.

Of the 10.5 million cars Toyota sold last year, it managed to flog just 24,000 electric vehicles (whilst Tesla sold 1.3 million EVs). The company’s much-touted yet improbably named bZ4X all-electric SUV suffered an embarrassing glitch after owners reported wheels falling off during drives.

The episode, addressed with a recall and quick fix, illustrates the possible predicament of the entire industry – and a repeat of how corporate Japan lost its edge in semi-conductors and consumer electronics. No Japanese car manufacturer features in the top-twenty for global EV sales. Industry analysts blame two bets Toyota made that went wrong: hybrid vehicles and hydrogen fuel-cells as the primary power source of EVs.

Too Much, Too Late

Toyota’s new CEO Koji Sato, formerly chief engineer at luxury brand Lexus, seems determined to play catch-up and has vowed to release no less than ten new EV models over the next three years and boost their sales to 1.5 million units by 2026. Meanwhile, Honda teamed up with Sony and plans a stable of up to thirty EV models by 2030.

The push may come too late with newcomers surging into the vacuum left by Japan’s industrial behemoths. Electrification has also significantly lowered the car industry’s formerly formidable barriers to entry – last successfully breached by Kia of South Korea.

BYD (Build Your Dreams) of Shenzhen, China, is hot on the heels (or bumper) of Tesla to become the world’s largest EV manufacturer. The company, founded in 1995 and in the vehicle business since 2003, can already claim that title if hybrid vehicle sales are included.

Complacency lurks as Prime Minister Kishida talks about a “new model of capitalism” but seems in no hurry to detail his ideas, let alone implement them. Japan – well organised, prosperous, harmonious, and largely content – feels no urgent need to define a vision, preferring instead to drift rather aimlessly towards the future.

It helps that the nation does not suffer political polarisation and has little time for populists. However, Japan’s cohesion and well-established pragmatism would seem to warrant and facilitate a more proactive approach to the issues at hand, lest Japanification is to gain a whole new meaning.

© 2023 Photo by Kampus Production