Rich Man, Poor Man: A Clash Foretold

Inequality on Steroids

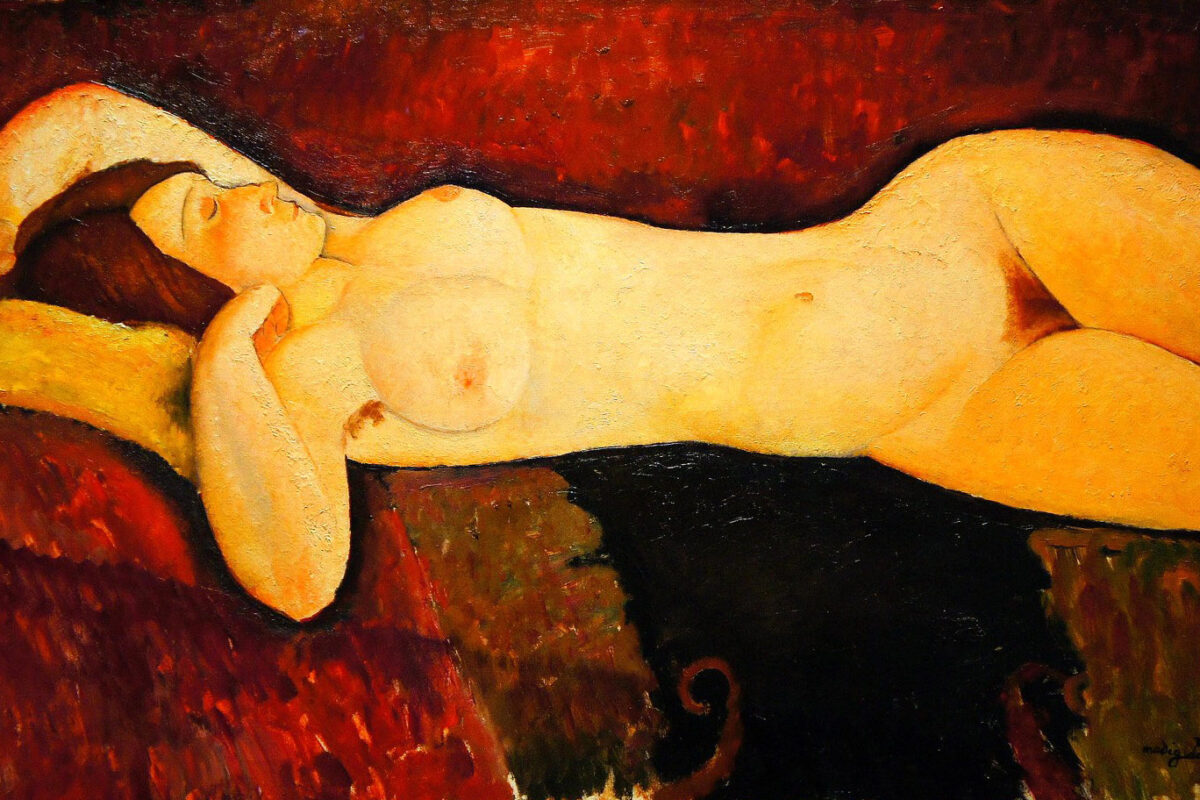

In November, a Chinese billionaire – one not yet clipped and cuffed at the order of President Xi Jinping – acquired Amedeo Modigliani’s Reclining Nude (1919) at an auction in New York for $170.4 million. It was the highest price ever paid for a painting with the sole exception of Pablo Picasso’s Women of Algiers (1995) – Picasso’s take on Eugène Delacroix’ original of 1834 – which earlier this year fetched nine million more.

Liu Yiqian (52) flashed his American Express card to pay for the canvas. The businessman, owner and chairman of the Sunline Group, is worth an estimated $1.4 billion and made his fortune in real estate and pharmaceuticals. He’s also a savvy stock trader and, as it turns out, a passionate art collector who recently opened his private museum in Shanghai’s historic downtown area to the public.

Last year, Mr Yiqian used his credit card to purchase a small porcelain cup made during the reign of the Qing Dynasty. He paid a cool $36.3 million for the trinket. Mr Yiqian then proceeded to use his newly acquired piece of chinaware to enjoy a cup of tea. Pictures of the billionaire sipping from the 500-year-old vessel that once belonged to Emperor Qianlong went viral instantly. The cup – sans saucer – is now on display in the museum.

Some people just have it and lack all compunction in flaunting their riches. New money wants to show off. Its owners, the aptly-named nouveau riche, need to assert control of their newfound station in life, near the very apex of humanity’s pyramid.

Mr Yiqian, a former cabbie, is but one of an estimated 215 billionaires in China. Though undoubtedly an astute and gifted entrepreneur, Mr Yiqian has also established a reputation for thoroughly enjoying the trappings of his elevated status by pursuing an extravagant in-your-face lifestyle. He did apparently not receive President Xi Ping’s memo on the poor taste of outward displays of opulence.

The Embarrassment of Riches

The embarrassment of riches is mostly lost on today’s billionaires. The phrase was originally coined by British historian Simon Schama to denote public morals in the 17th century Dutch Republic1. While the rich were widely admired for their accomplishments, any public display of wealth met with sharp disapproval. This Calvinistic take on the behavioural responsibilities of the well-heeled has been replaced by shameless voyeurism in which the have-nots drown their own misery gaping at the profligate haves as they play with expensive toys and dwell in palatial mansions whilst showcasing both material excess and intellectual dearth.

The public’s admiration is largely reserved for the idle rich – the likes of Paris Hilton and her former sidekick Kim Kardashian – and for too-rich-to-fail attention-seeking losers such as Donald Trump. Only a few really big earners, mostly self-made American billionaires, realise that money isn’t everything and give away their fortunes for the betterment of society. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg last November joined Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, Larry Ellison, Michael Bloomberg, and other über-rich in a pledge to donate the bulk of their wealth to noble causes. Interestingly enough, most American billionaires have no need to either hoard or flash their riches with Mr Buffett even putting in an appeal for the government to tax him more.

Mr Buffett, worth an estimated $66.7 billion, had noticed that his secretary pays a larger percentage in taxes on her earnings than he does. Even without aggressively pursuing tax avoidance via the esoteric, though legal, fiscal structuring of deals and businesses, Mr Buffett was unable to jack up his tax bill.

Where even a billionaire willing to pay society its due is stumped, there is a problem of sorts: a distributive system hijacked and derailed by less generous and/or grateful wealthy individuals and corporations that fail to appreciate – either through malice or ignorance – the inner contradictions of capitalism. Mr Buffett is not one of them and fully understands that his gift for accumulating vast quantities of wealth would have proved of little practical use in a society unhinged by disorder, strife, lawlessness, poverty, or any other disturbance.

Mao’s Axiom

Given that, ultimately, political power indeed grows out of the barrel of a gun, the few rich exist by the grace of the many poor. As long as the multitude believes there to be a reasonable chance to strike it rich – by hard work, genius, talent, or plain luck – a solid social equilibrium is maintained. Prospering societies recognise that not everyone is wired for success and some of its individual members will inevitably lag behind whilst others may only barely scrape by. The vast majority is usually able to fare relatively well, leading comfortable lives without suffering dramatic ups or downs.

The meaning of life: to stay happy and carry on.

The US Founding Fathers had figured as much in 1776 with their Declaration of Independence which states that all human beings have an unalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Jefferson et al also stated that governments derive authority (‘are created’) from their duty to protect these rights. While legal scholars have dissected, analysed, and reinterpreted each and every word of the document ad nauseam, the US Declaration of Independence still is one of the boldest and clearest – and most revolutionary – statements ever on the function of government.

However, as of late, governments have suffered from mission creep. For entire demographic swaths, the pursuit of happiness has been largely reduced to an increasingly desperate fight for survival on the periphery. Rising inequality has swelled the margins around a shrunken core of society where decisions are made, fates sealed, and wealth is accumulated. Admittance to this core of plenty is now severely restricted.

The Pew Research Center – a non-partisan US think-tank from Washington DC that primarily conducts empirical social research – found in a 2014 study that, for the first time in history, most Americans think children will be financially worse off than their parents. Overall, close to 61% of people queried fear the next generation must take a step back or not see any gains. The findings were remarkably even across all age groups and income brackets although Tea Party members were a bit more optimistic – or in denial of reality – than most. The pessimism is not confined to the United States. Similar results were found in ten out of thirteen advanced nations polled.

America’s middle class – of Bewitched and Doris Day fame – is rapidly disappearing. Its share of the nation’s aggregate income dropped from 62% in 1970 to barely 43% last year. Increasingly, Americans are either rich or poor with entrance to the upper-income echelons reserved for the asset-rich – the proverbial fortunate sons, made to wave the flag, born silver spoon in hand. Pew’s research found that a college degree is no longer the passport that ensures access to middle America. Instead, a university education provides a life-long drag on asset accumulation with young people entering the workforce burdened with student debts often exceeding $100,000.

Nowhere to Stake a Claim

Another reason why the up-and-coming generation cannot easily outperform the previous one is that it has nowhere to stake its claim: in most industrialised nations, affordable housing has now become a distant memory. In the UK, the average price of a single-family home in 2015 reached £272,000.

According to the Halifax House Price Index, residential real estate prices have shot up by close to 400% since 1986. Unsurprisingly, wages have not kept pace. Numbers from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) show that over the past two decades average, hourly earnings have only increased by about 220% – or at about half the rate homes appreciated in price.

Even so, this already sour statistic nugget paints a rather distorted picture since it fails to account for sharply increased income disparities. People stuck in the bottom ten percent of the pyramid make do with an average annual net income just shy of £8,500, while the take-home pay of the top ten percent of earners amounts to a whopping £79,000 – almost ten times as much. The concentration gets worse still with the top one percent enjoying an average after-tax income of almost £260,000 per year.

Subsisting on an exceedingly modest income that barely covers life’s basic necessities does not allow for the creation of any discernible wealth. Thus it is that the less fortunate 50% of UK households only hold 9.5% of the nation’s wealth. Life in the top decile is backed up by no less than 44% of the country’s wealth.

If Credit Suisse is to be believed, this polarisation in wealth levels is set to increase dramatically. In a 2014 report, the bank’s number crunchers conclude that most asset classes will undergo a 40% revaluation over the next five years. Owning a house is still the path of least resistance for those who wish to become millionaires. With property prices reaching stratospheric heights, the UK between 2013 and 2014 produced well over 500,000 fresh millionaires most of whom arrived at their new station in life via the comfort of the living room chesterfield.

London council houses, that once had the local gentry thumbing their noses at the presence of the uncultured masses, are now widely praised for their spaciousness and privileged location. Some have already fetched upwards of a million pounds. The dreadful Trellick Tower in North Kensington – formerly a 31-storey-high den of vice and crime, designed, appropriately enough, in the brutalist style of the late 1960s – has turned into a most fashionable address, and a cult landmark to boot. Here buyers readily shell out half a million pounds or so for a flat formerly inhabited by the downtrodden.

Demographic Cleansing

The people for whom these estates were originally built have mostly been expelled from central London – only a few resisted the temptation to buy their homes from the local council and managed to maintain a toehold in the city. Whilst an extreme example – or warning – London is not alone in ceding to gentrification. Starters or laggards in Amsterdam, Brussels, Paris, Frankfurt, Stockholm, and many other large cities are either unable to find housing that fits their budget, or are being prodded to make way for the movers and shakers.

In some German cities, houses are now so far out of reach for the common man/woman that banks have launched a new product to address the issue: the multigenerational mortgage – a loan running for forty years or longer. Such mortgages are already common in Japan and may see their debut in the UK before long.

At the other end of the scale sit Spain and Portugal where millions of homes stand empty – the flotsam of a construction boom gone bust and a recession that failed to recede. Millions not only lost their jobs to the Great Recession but were evicted from their homes as well, unable to keep up with mortgage payments. In Spain, an archaic bankruptcy law with a large punitive element, threatens to keep an entire generation shackled to debts incurred at the height of the property boom that are now simply impossible to clear.

With governments across Europe adhering to fiscal orthodoxy as if it were a state religion, and cutting social welfare programmes to the bone in the name of smart spending, the lower half of society need not expect improvements in its fate any time soon. The working poor – a demographic not seen since Victorian times – have returned with the number of jobs not providing a living wage rising exponentially.

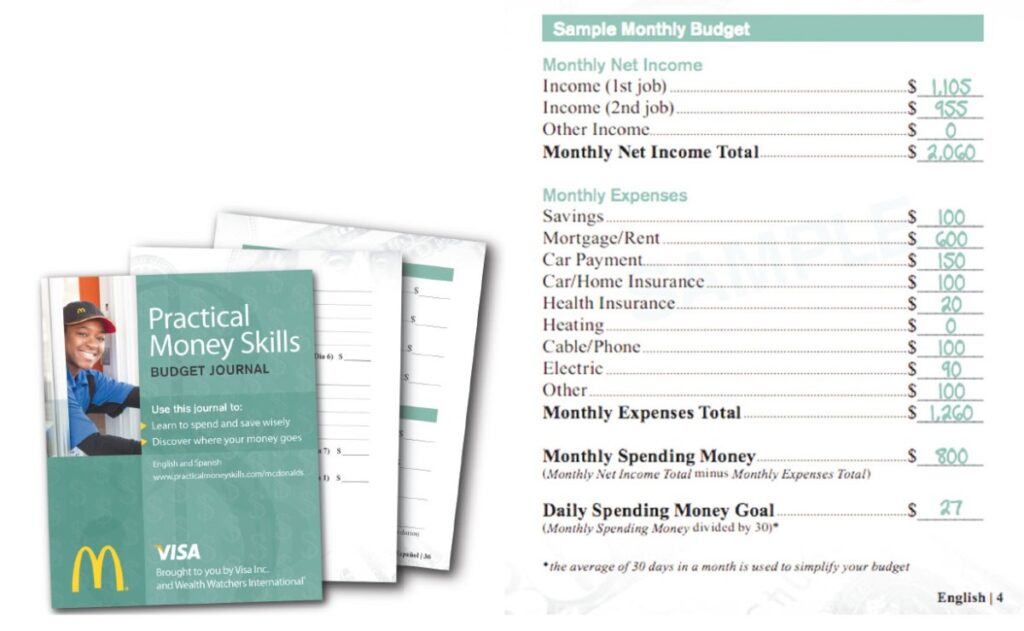

In the US, workers at hamburger restaurants and big retailers cannot make ends meet even when putting in full shifts and overtime. In an attempt to improve the financial literacy of its workers, the management of McDonald’s brought in experts from Visa to help design a model household budget only to conclude that the exercise was impossible without including income from a second job. The ideal expense budget they subsequently produced failed to include heating costs and a clothing allowance. It did contain a monthly $20 for healthcare expenses, even though the most basic of health plans offered by McDonald’s costs its employees $14 per week.

Life in an Ivory Tower

Today’s corporate and government leaders are largely confined to their ivory towers. In their self-imposed exile from the society they exploit or rule, many lose touch with reality. British Prime Minister David Cameron seems particularly estranged from real life as he merrily cuts and slashes away at the welfare state, only to wonder why public services are deteriorating at such an alarming speed.

In a letter that found its way to the press, Mr Cameron chided the leader of the Tory-run Oxfordshire county council Ian Hudspeth for considering deep cuts to public services such as libraries, museums, and day care facilities for the elderly. Mr Cameron argued that the ‘slight fall’ in government grants to the council does not justify the reduction of frontline services on the scale now proposed.

In his reply, Mr Hudspeth reminded the prime minister that Oxfordshire council has seen its funding reduced from £194 million in 2009 to £122 million in 2015 with further cuts already announced. Mr Hudspeth also noted that while the council’s grants were reduced by £72 million, it also received additional responsibilities in public health and social care. “I cannot accept your description of a drop in funding of £72 million, or 37%, as a slight fall,” Mr Hudspeth concluded.

The growing divide between the haves and have-nots breeds misunderstanding on a grand scale as both worlds drift apart and the bridge that connects them – the middle class – narrows. In his monumental Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century2, French economist Thomas Piketty needs 696 pages to show that capitalism works precisely as advertised: it creates capital by concentrating wealth into ever fewer pockets. Left to its own devices, capitalism rewards the owners of assets more than it does those who live by the sweat of their brow.

What Mr Piketty proves by distilling historical data, Karl Marx had already deduced by applying his formidable powers of reasoning and logic. In his 1847 work Wage-Labour and Capital3, Mr Marx shows how economic development deprives labour of its human dimension to become a mere commodity.

Goldilocks Found and Lost

It took a great many revolutions and other upheavals for politicians and economists to find the goldilocks zone between capital and labour – that narrow strip of thought straddling the two extremes, able to deliver lasting prosperity to all. They called their epiphany social-democracy.

While a few countries dabbled in social-democracy before the Second World War, the system was wholeheartedly embraced only after the conflagration had subsided and an entire continent had been laid to waste and needed prompt rebuilding. This was not the time to act out tiresome conflicts between capital and labour.

Governments intervened decisively and forcefully to set entire societies to work and regain a modicum of prosperity. Strict limits were placed on both capital returns and wage increases. This, and the sensible approach to evening out booms and busts prescribed by British economist John Maynard Keynes4, produced a revival the likes of which had never been seen before: from the smouldering rubble of bomb-flattened cities a New Jerusalem arose.

The power of austerity politics was leveraged not to rescue a few incompetent bankers, but to rid whole societies of want. In less than twenty years, the ravage wrought by the most savage of wars had been cleared. Business was not just booming; it contributed – through comprehensive taxation – to a general state of well-being. Whilst opulence was outlawed, so too was dire poverty via just the right amount of income distribution.

What makes Mr Piketty’s research into the relation between capital and labour so ground-breaking is that the French economist carefully charted how the post-war equilibrium – the formula of success – was slowly disassembled as memories of that era faded and capital reasserted its pre-eminence.

Contemporary economists – preoccupied with maximising profits, either national or corporate – show disdain for both the work of John Maynard Keynes and anyone else daring to suggest that their science – or dark art – ought to prioritise the pursuit of human happiness and fulfilment over stats, tables, and projections. That, however, is no longer a given. Laissez-faire has returned to the fore with a vengeance.

The Return of Laissez-Faire

Even a Nobel Prize winner is allowed to make a few mistakes every now and then. University of Chicago economist Robert Lucas certainly got it wrong when he proclaimed in 2003: “The central problem of depression-prevention has been solved, for all practical purposes, and has in fact been solved for many decades.” Not five years later, Lehman Brothers folded; an event that triggered a prolonged global economic downturn and thus offered irrefutable proof that humanity had still not managed to extirpate the boom-and-bust cycle from its collective endeavours – otherwise known as the economy.

Professor Lucas, winner of the 1995 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences and hailed as one of the world’s most gifted macroeconomic thinkers, has published a number of works that question the wisdom of using policy to steer economies in the desired direction. Prof Lucas argues that historical data are a poor guide for predicting policy outcomes.

In a phenomenon akin to the observer effect – whereby an object’s characteristics change merely by being subjected to scrutiny – the Lucas Critique states that the body of optimal decisions taken by economic agents constitutes a fluid econometric model: policy initiatives aim to modify the model’s structure and thus cause optimal decisions to shift. This inevitably changes the overall econometric model which now no longer corresponds to the one that served as the premise for the policy.

Essentially, Prof Lucas suggests that all economic policies are destined to fail if they are inspired by historical data. With this in mind, Prof Lucas concluded that “of all tendencies that are harmful to sound economics, the most seductive, and the most poisonous, is to focus on questions of distribution.” Tinkering with the division of the pie would make it only smaller.

In the face of an overwhelming body of evidence, that conclusion is no longer held to be true. Whilst in theory Prof Lucas may be right, empirical data spanning centuries show that inequality severely undermines growth and, indeed, reduces an economy’s potential to prosper. Ensuring the equitable distribution of whatever size pie available offers a shortcut to development.

IMF Weighs In

A study released earlier this year by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) concludes that trickle-down economics – the notion that rewarding the already rich ultimately benefits all of society – is a fallacy. In Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality, IMF researchers find that when the rich get richer, economic growth in fact slows down. Conversely, when a country’s poor manage to increase their share of national income, economic expansion speeds up noticeably.

Progressive tax systems, financial inclusion, and raising human capital and skills all contribute to accelerated development and are now considered potent tools for ending world poverty. IMF Director-General Christine Lagarde tries to move the discussion regarding income inequality and wealth disparity from the realm of politics to the sphere of economics – where it belongs: “Lifting the income of the poor is not about altruism. Rather, it constitutes an essential element of any policy aimed at generating higher and more sustainable growth.”

IMF researchers found that a one percent increase in the income share of the poor will boost GDP growth by 0.38 percentage points whereas allowing the rich a one percent larger share of national income results in a 0.08 percentage points decrease of economic growth.

These figures prove what some have been proclaiming all along. Joseph Stiglitz, winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2001 and professor at Columbia University, has been one of the most vociferous critics of rising inequality.

Stiglitz to the Rescue

In his 2012 book The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future5, Mr Stiglitz shows that inequality is a self-perpetuating phenomenon and, while at it, exposes the myth of free markets which, he argues, do simply not exist – and never have.

Where Thomas Piketty uses historical data to underpin his conclusions, Joseph Stiglitz takes the argument a few steps further stating that wealth not only attracts more wealth, but buys political power as well. “Whilst there may be underlying economic forces at play, politics have shaped the market, and shaped it in ways that advantage the top at the expense of the rest.”

Mr Stiglitz goes on to accuse the rent-seeking classes for causing inequality by exploiting monopolies, incurring favours from governments, and refusing to pay their fair share of taxes. He makes short shrift of both neoliberal Democrats and laissez-faire Republicans by pointing out that both aim to rig the market.

In particular, Mr Stiglitz inveighs against the reduction of estate taxes and the deregulation of campaign financing laws. The former facilitates the formation of an aristocracy – against which the Founding Fathers had explicitly warned – whilst the latter allows corporations to acquire political power. This, Mr Stiglitz concludes, stifles competition and makes markets less free still.

Income and wealth disparities not only undermine democratic political life, they also detract from overall prosperity. In his book, Mr Stiglitz points out that excessive inequality creates volatility, fuels crises, decreases productivity, and stuns growth. In a blog, Mr Stiglitz recently summarised his findings: “Lack of opportunity means that an economy’s most valuable asset — its people — is not being fully used. Many at the bottom, or even in the middle, are not living up to their potential, because the rich, needing few public services and worried that a strong government might redistribute income, use their political influence to cut taxes and curtail government spending.”

This reduced spending on the common good, in turn, leads to systemic underinvestment in infrastructure, education, public health, justice and other public services that together form the engine for sustained growth. When that engine falters, economic expansion slows down and gaps in income and wealth widen.

Despite decades of moderate growth, the purchasing power of the average wage has remained stagnant for almost fifty years. The inflation adjusted average income of the middle quintile has advanced only 23% since 1967 while labour productivity almost tripled over the same period. Worker compensation per unit of output has thus decreased a staggering 55%.

The gains in productivity, derived mostly from technological innovation, flow directly into the pockets of asset owners. Even those in the top quintile of income earners only saw their purchasing power augmented by 76% over the last half century. Predictably, those in the bottom quintile fared worst of all, gaining slightly less than 18%.

These numbers represent a trend break. Data from the US Bureau of Statistics show that between 1947 and 1979, increased non-farm productivity was matched by a corresponding jump in average hourly compensation. However, from 1980 onwards this linkage was lost. In 2013, the last year for which data has been compiled, workers’ share of productivity gains amounted to less than 15%. The rising tide lifts some boats significantly more than others.

Misperceptions

Inequality is worse than most people think. Professor Michael Norton of Harvard Business School unearthed a case of mass delusion in a 2014 study6 in which he examines the public’s perception on executive pay. Prof Norton and co-author Sorapop Kiatpongsan of the University of Chulalongkorn in Thailand first show that for most of the 1960s the typical American CEO earned about twenty times the money paid to the average Joe or Jane plugging away on the work floor or at the office. Today, the man or woman at the top hauls away anywhere between 274 and 354 times more than the median working stiff, depending on who supplies the numbers.

Now for the interesting bit. Asking some 55,000 people around the world how much they thought top executives make, most American respondents guessed that the CEO takes home around thirty times the amount paid out to average workers. They also believe a more appropriate level of compensation would hover around the 7-to-1 mark.

“In sum, respondents underestimate actual pay gaps, and their ideal pay gaps are even further removed from reality than those underestimates,” write Messrs Norton and Kiatpongsan. Emboldened by his findings, Prof Norton then went on to ask Americans how they would picture the ideal distribution of wealth throughout society.

When the data came back it showed that most Americans actually seem to prefer a distinctly North European model in which few get left behind and fewer still may enjoy untold riches. In fact, 92% of respondents opted for the Swedish model of income distribution.

Most people also seriously underestimate the amount of wealth amassed by those at the top. Prof Norton’s research found that respondents estimated that the top 20% of US households collectively owns about 59% of the nation’s wealth while in reality that quintile claims 84% of the marbles. In an ideal world, Americans think the top fifth of society should contend itself with about 32% of all wealth.

“People drastically underestimate the disparities in wealth and income and their ideals are more equal than their estimates, which are already more equal than the actual levels. People from all walks of life – progressives and conservatives, rich and poor, all over the world – have a large degree of consensus in their ideals: everyone’s ideals are more equal than they actually think they are,” concludes Prof Norton.

It gets even funnier when these findings are matched to voter behaviour. Polling firm Gallup consistently reports that a majority of Americans are in favour of a more even distribution of both wealth and income. However, few believe that the rich should be taxed any more than they already are. While the Pew Research Center found that 45% of registered Republican would like the government to intervene and ensure a more equitable distribution of the nation’s wealth, few, if any, of them dare come out and say so openly.

Social Immobility

One of the main reason why taxing the rich to the hilt constitutes such an unpopular proposition is that quite a few people aspire to join the rarefied atmosphere where the haves-all dwell. Nobody fails to get touched or inspired by a well told rags-to-riches story. The chance of reaching those great heights of vast material well-being are, however, becoming ever slimmer.

Social mobility in both the UK and the US has descended to historical lows. Figures from the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development) show that both Britain and the United States score particularly low when it comes to lifting people out of poverty. Of late, they seem much better equipped to tilt the demographic in the opposite direction.

With education being the greatest of all equalisers, restricting access to colleges and universities contributes, more than anything else, to a reduction in upward social mobility. Whereas in the 1970s, every university student from the bottom quintile studied in the company of four peers from the top fifth of the income pyramid, by the 1990s that number of affluent students had grown to six. Perhaps mirroring the decline in the quality of state schools, aspiring students from lower income groups are about half as likely to gain entrance to universities as their peers with parents in the higher income brackets.

The privileged classes do protect their domain: fully seventy percent of the UK’s high court judges enjoyed an education at private schools that dispense knowledge to only seven percent of the country’s overall student population. A private education is also essential to break into the top management of TFSE-100 companies.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation, which promotes social change through policy research, concluded in a 2013 study that more than half the intergenerational transmission of income occurs through education: “A failure to broaden access to cognitive skills is an important part of intergenerational inequality persisting across generations in highly unequal societies such as Britain.”

Former British Prime Minister Sir John Major was a lone voice in the wilderness of Tory politics when in 2013 he called it ‘truly shocking’ that the well-heeled private school educated upper echelons of society still dominate public life. The Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission, charged with monitoring the government’s progress on both issues, discovered that low-ability children from affluent households already after their first few years in school outperform high-ability kids from poor families.

However, change is not impossible. Not ten years ago, London state schools were counted amongst the worst in the country, producing mostly functional illiterates. Today, after a sustained effort by council administrators, teachers, and parents, these schools have become veritable temples of learning and breeding grounds for success.

Equality in Moderation

Whilst it is satisfying to think that all are equal and, thus, nobody is inherently better than their peers; too much equality is not necessarily beneficial. Experiments at imposing equality top-down have mostly resulted in bland – and repressive – societies that stifle human ingenuity and discourage both innovation and initiative.

The drab German Democratic Republic – now thankfully extinct – comes to mind as does the collective madness known as the Cultural Revolution that ruthlessly stamped out any and all bourgeois tendencies in China – and reaffirmed Chairman Mao’s power – at a cost of an estimated two to three million lives.

Writing for the Cato Institute, a libertarian think-tank in Washington DC, researcher Swaminathan Aiyar warns that excessive equality is as dangerous – if not more so – than high levels of inequality. Mr Aiyar parades a host of (ex-)countries that elevated egalitarianism to almost religious-like status and saw their people leave in droves.

Thousands of Cubans braved the shark-infested water of the Florida Straits on makeshift rafts to try their luck in the land of the unequal, coincidentally also home of the brave. Thousands suffered a similar ordeal fleeing Mao Zedong’s China to reach Hong Kong – one of the most unequal places in the world.

In between both extremes are a few countries that have managed to avoid societal polarisation. For the best chance to advance in life, look at Denmark which now generates more rags-to-riches stories than any other country in the world, relative to the size of its population. The streets of Copenhagen are paved with gold: a Danish child from the poorest quintile has twice as much chance (19%) at making it to the top than an American kid does from a similarly disadvantaged background.

Clashing Values

The countries that sustained steady economic growth since the end of World War II, and delivered genuine prosperity throughout society, are precisely the ones that resisted the temptation to treat labour as a mere commodity and, by doing so, refrained from discriminating either capital or labour in the allocation of political power. What seems so simple – an economy in order to produce added value needs inputs of both capital and labour – degraded into a shouting match with all sides claiming primacy.

When Karl Marx expounded on the balance between the two, he rightly surmised that capital and the forces of supply and demand would ultimately prevail – before, of course, succumbing to their inner contradictions. The latter part never did quite pan out. Whilst Karl Marx and David Ricardo – and a few anarchist thinkers such Pierre-Joseph Proudhon – tinkered with the labour theory of value, which prices goods and services by the amount of labour required in their production, Adam Smith had already figured out that economic value is a mere function of the ‘toil and trouble of acquiring’ the desired good or service. Put bluntly: a device that ‘rewinds’ CDs and DVDs7 has no value since it serves no discernible purpose and generates no demand. The amount of labour that went into its production is therefore irrelevant.

Troubles escalated when the Austrians got involved with their methodological individualism which – amongst a great many other things – holds that value may merrily be created out of thin air. Léon Walras et al elaborated on a phenomenon already observed and described in the Middle Ages: value is added when goods pass to a buyer who attaches greater worth to it than the seller does.

Such a transaction adds value although the traded goods as such are not modified in any way. These deals are mostly self-sustaining and keep adding value to any given product or commodity, pushing prices ever higher, until someone wakes up to the fact that the emperor hath no clothes. This is when the market crashes – or ‘corrects’ in the parlance of the pundits – only to resume its upward trend before long.

The Austrian School of economic thought forms the bedrock on which modern capitalism – up to and including obscurantist practices such as high frequency trading – has been erected. Expunged of its human dimension (labour), the creation of value (wealth) largely became an exercise in the abstract. With asset owners no longer in need of labour to grow their holdings, the value of work diminishes – obeying the iron-clad law of supply and demand. Thus, the mutual dependency between capital and labour was broken; the former no longer needs the latter in order to prosper.

Economies may now grow – if not prosper – without benefiting the masses, resulting in the stagnation of wages and unusually high levels of unemployment. This large pool of idle labour ensures fierce competition for the jobs that are created, further depressing worker compensation. In case of a ‘hot’ labour market, borders swing open to import workers. Add free cross-border trade to the mix – effectively depressing wages to the lowest denominator – and a widening gap in wealth and income distribution is unavoidable.

The Return of the Jacobins

That gap is already mind-bogglingly wide. Global development aid network Oxfam last year calculated that in 2016 the richest 1% of the world population owns an amount of wealth equal to the combined possessions of the remaining 99%. Elevating this statistical mischief onto an even higher pane, Oxfam also pointed out that the world’s richest 85 individuals – a double-decker busload of billionaires – command as much wealth as much as the poorest 3.5 billion of the world’s inhabitants together.

Most economists tend to agree that too much inequality harms development and undermines overall well-being by conspiring against the efficient use of human resources. Societies derive few benefits from harbouring masses of unemployed and/or undereducated people. Rather than serving purely for the accumulation of wealth – and the interests of the few – economies can only expect to remain sustainable if they are inclusive and further the common good.

Failure to ensure a reasonably equitable distribution of both wealth and income is akin to inviting the Jacobins to return and mobilise their sans-culottes. Ultimately, a busload of whimpering billionaires is no match for 3.5 billion or so deprived people who have woken up to the fact that the system is squarely rigged against them.

Inequality on the scale currently experienced cannot be sustained indefinitely. As Thomas Piketty noted and proved, more equal societies only come about after some conflagration of epic proportions – war, revolution, or natural disaster – hits home and shows all human beings to be equally frail in the face of adversity. Equipped with both knowledge and technology, and armed with plenty experience as well, class war – to use a term half-forgotten – need not again erupt.

As the group of American billionaires coalescing around Warren Buffett has shown; wealth is not all it is trumped up to be if kept in a vault. Spreading it around a bit not only keeps the pitch forks in the shed, but also allows the select few to do what they do best: set an example for the rest of us to follow – and aspire to.

Cover photo: Reclining Nude (c. 1919) by Amadeo Modigliani (1884-1920) bought for approximately $170 million by Chinese billionaire collector Lui Yiqian.

Footnotes

- The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age by Simon Schama. (Harper Perennial, 2004) – ISBN: 978-0-0068-6136-2.

- Capital in the Twenty-First Century by Thomas Piketty (Harvard University Press, 2014) – ISBN: 978-0-6744-3000-6.

- Wage-Labour and Capital by Karl Marx (Wildside Press, reprint 2008) – ISBN: 978-1-4344-6926-7.

- The Essential Keynes by John Maynard Keynes (Penguin Classics, 2015) – ISBN: 978-1-8461-4813-2.

- The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future by Joseph E Stiglitz. (WW Norton & Company, 2013) – 978-0-3933-4506-3.

- How Much (More) Should CEOs Make? A Universal Desire for More Equal Pay by Michael I Norton and Sorapop Kiatpongsan – Perspectives on Psychological Science volume 9, issue 6, November 2014.

- The DVD Rewinder – ‘based on a centripetal velocity engine’ – was actually produced and marketed by American entrepreneur Bill Wimsatt in 2009. Mr Wimsatt is no longer in business.

- © 2012 Photo Reclining Nude by Regan Mercurysse

- © 2008 Photo Trellick Tower by Steve Cadman

- © 2011 Photo John Maynard Keynes by Patrick Chartrain

- © 2011 Photo John Major by Chatham House

- © 2020 Photo studious Chinese peasants by Manhhai